In this blog, I am currently discussing the medieval church as found in my West Country Medieval Mystery Series featuring my heroine, the Lady Apollonia of Aust. I began with medieval cathedral churches, then focused last month on Glastonbury Abbey, one of the wealthiest and most important abbeys at the time of my stories. This month I would like to shift to another English monastic church, Saint Mary’s Abbey in Cirencester, Gloucestershire. This abbey plays a major role in my fourth book, Templar’s Prophecy.

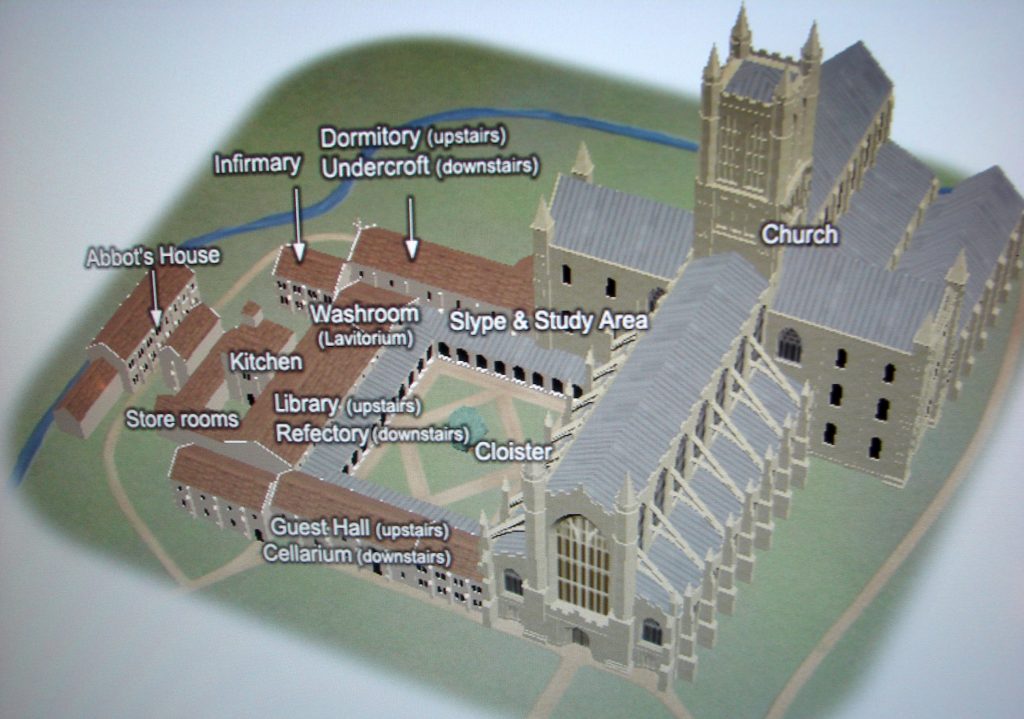

Unlike Glastonbury Abbey, there are no ruins surviving above ground for the monastic buildings that once stood in Cirencester. A model of the medieval monastery, shown above, is on display at the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. Some of the original abbey walls still exist as does one of the gates, the Norman Gate which is shown just below. The abbey wall next to the parish church is shown beyond that. Even further below is the grass parkland where the abbey church stood. Flat stones outline the church walls while the bases of the interior columns are just visible.

The present abbey church was begun in 1117 with help from King Henry I. It was dedicated in 1176 and was already an Augustinian monastery on the site of what is reputed to be the oldest known Saxon church in England. Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, it became more powerful, wealthy, and began to dominate the local economy, controlling the local markets for example.

This led to tension between the abbey and the town in the 14th century, much of which came to a head in the last decade of that century when Templar’s Prophecy is set. This tension between the monastery and townsfolk is something I have described in my novel. Many of the monks of Saint Mary’s Abbey play significant roles in this story, more so than monks in any of my other Lady Apollonia books.

Saint Mary’s Abbey in Cirencester ceased to exist in 1539 with King Henry VIII’s dissolution of all monastic institutions. The stone buildings represented in the model at the top of this posting were thoroughly quarried and reused locally. Some of the stone went into Abbey House which was built and later rebuilt on the grounds of the abbey. Abbey stone also went into other buildings in town, some of which have signs to indicate this reuse.

Other traces of the abbey can be found in and around Cirencester. A dovecot and an abbey tithe barn, shown above, can be found on the outskirts of the town at Barton Farm. Such buildings were valuable for use apart from the monastic enterprise and often survived the dissolution of the monasteries.

There are numerous steams running through the town and into the abbey grounds. These are reminders that Cirencester Abbey, like many monastic institutions, was quite dependent on water, not just for daily life in the abbey but also to run its mills. A picture of one of these streams is shown below.

Recently, I have talked about major medieval monastic churches in my stories. Next month, I will describe some of the lesser monastic institutions known to the Lady Apollonia in her 14th century adventures.