As I arrived at Douglas Land Conservancy, I was full of questions about the upcoming summer. There were many unknowns, but perhaps the biggest question on my mind was about the purpose of my summer at DLC. Ever since I stepped foot on campus at Valpo, I had been acutely aware of the university’s focus on and attention to service. Service is an integral part of university life. Soon after I learned of my placement at DLC, I was filled with questions about the conservation field, and its relationship to service. I spent much of my first week pouring over files, attempting to gain a basic understanding of the conservation field. For those of you as unfamiliar with the field as I was, I will give you a quick flyover of what I’ve learned so far.

The kind of work that DLC does on the land can be broken down into two categories: private and public. The organization holds conservation easements, which are legal agreements that state that the land in question is to be protected in perpetuity, on specific parcels of land. Some of these easements are for public open spaces, where anyone can come and enjoy all that the land has to offer. Other easements are on private land, with the land owner retaining ownership of the land, but giving up any developmental rights. These kind of easements are put in place to protect wildlife habitats, scenic viewscapes, as well as a myriad of other reasons. DLC is constantly partnering and working with other conservation organizations to protect property throughout Douglas County. With these different kinds of easements that DLC holds and protects on our minds, now I want to dive into the question that has been on my mind constantly this summer: Is this work service?

I have been at DLC for just over a month, and I have learned an incredible amount of information, and have been digesting all that I have learned. In my mind, conservation is absolutely a form of service. I think that many times we limit our view of service because we focus on a particular kind of service, which is helping those in dire need of something. Of course, there is absolutely nothing wrong with that kind of service, and we should praise those who work to do just that. Simply put, my summer at DLC has challenged if that is the only kind of service that there is. During my internship, I have not helped a needy family, listened to an immigrant’s story, or combated modern day slavery. The majority of people that I have interacted with are fairly well off white people. And yet DLC, and other land conservation organizations, are deeply committed to service. This kind of service may not fit a typical definition of what service is, but land conservation is absolutely beneficial to society at large. In a world where so much seems to be about the bad, land conservation organizations are working hard to preserve what is good. One of my favorite historical figures is John Muir. If you have not heard the name, I encourage you to check him out. Muir was an early advocate of wilderness protection, specifically in the Western United States, and is known as the Father of the National Parks. He spoke about the healing qualities of the natural world, and how each person needs time in nature to nourish his or her soul. It is that kind of experience, and that kind of nourishment, that DLC is actively protecting, specifically through public open spaces.

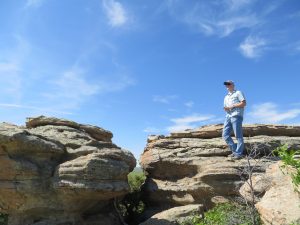

During my time at DLC, I have spent a good amount of time out on the land, whether it is monitoring protected properties or joining guided hikes on protected open spaces. And it is there, when one is surrounded by creation, that the impact of DLC’s service fully manifests itself. There is something so special and unique about open spaces. The protected space is open to all. Many of these open spaces are considered prime real estate, and could have easily ended up 35 acre parcels with a magnificent house on each section, complete with awe-inspiring views. But instead, these lands are under protection for perpetuity. And that is a good, beneficial outcome. Service does not simply have to be about fixing a wrong, it can be about preserving a right. The open space will remain open to the public, allowing people of all walks of life a brief respite from the hectic pace of the world, and a chance to nourish their souls, as Muir would have wanted. The privately owned properties will retain their natural character forever. In a world where development can spread like wildfire, the preservation of the character of the land is critical. Conservation organizations are working to protect and steward creation in its natural form, and attempt to minimize the impact that we humans will have on the land.

The most beneficial part of my summer has been the intensive kind of thinking that I have found myself engaged in each and every day when I am out on the land. Thanks to what I have learned at Valpo, I am applying my previous knowledge to my current situation, and it is leading to an incredible amount of self-reflection. I look at things in a manner that I would not have three years ago, and I credit Valpo for helping me develop a deeper sense of questioning of the world around me. My time at DLC has left me contemplating a set of questions that I had never encountered before. There are still parts of the conservation field that weigh heavily on my mind, specifically when it comes to private lands. The public benefit is clear when one looks at open spaces, but is more obscure and refined when it comes to private easements. How I incorporate that aspect of land conservation into my conception of service that my time at Valpo has sparked in me has been a continued challenge this summer. I am excited to continue this journey over the summer, and to continue self-reflecting on the difficult questions that I encounter.

day when I am out on the land. Thanks to what I have learned at Valpo, I am applying my previous knowledge to my current situation, and it is leading to an incredible amount of self-reflection. I look at things in a manner that I would not have three years ago, and I credit Valpo for helping me develop a deeper sense of questioning of the world around me. My time at DLC has left me contemplating a set of questions that I had never encountered before. There are still parts of the conservation field that weigh heavily on my mind, specifically when it comes to private lands. The public benefit is clear when one looks at open spaces, but is more obscure and refined when it comes to private easements. How I incorporate that aspect of land conservation into my conception of service that my time at Valpo has sparked in me has been a continued challenge this summer. I am excited to continue this journey over the summer, and to continue self-reflecting on the difficult questions that I encounter.