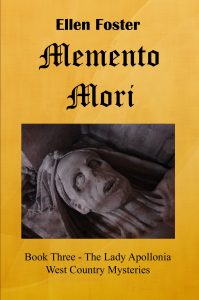

The last blog posting completed my discussion of the ancient city of Gloucester in Memento Mori, my third novel in the Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries Series, whose cover is shown above on the left. Now I wish to discuss other topics addressed in this book beginning with Death and Plague, topics much related in the 14th century setting of my books.

The last blog posting completed my discussion of the ancient city of Gloucester in Memento Mori, my third novel in the Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries Series, whose cover is shown above on the left. Now I wish to discuss other topics addressed in this book beginning with Death and Plague, topics much related in the 14th century setting of my books.

Throughout history there have been major occurrences of what we now call the Bubonic Plague, transmitted by fleas often found on rats. The sheer number of rats and their contact with humans became the vector for the disease to jump from animals to humans. Two major outbreaks of plague have been in Europe: the first was in the 6th to 8th centuries and was known as the Plague of Justinian, the emperor who contracted the disease after its arrival in Constantinople in AD 542. Justinian was one of the few lucky enough to survive it as between a quarter and a half of the population were killed by the disease in this occurrence. See my earlier posting of May 16, 2017 in the archives below on the right for more information on the Bubonic Plague.

Major occurrences of the plague came to Europe in the middle ages in multiple waves. The first wave, called the Black Death at the time, struck England in 1347 with several repeat visits before 1392 when my Memento Mori novel was set. These waves, a devastation which affected almost everyone, wiped out a third to a half of the total population of the country. Subsequent waves of the plague returned to England for three more centuries and even spread to colonial America.

One of the effects of the 14th century plague in England was an emphasis on creating tombs decorated by full length carvings of decaying bodies in churches. These were obviously remembering one’s death, or “memento mori” in Latin which I have used as my title. Such tombs were nearly always accompanied by a threatening poem:

Listen man, as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I;

As I am now, you soon shall be

Prepare therefore to follow me.”

However, a cheeky widow in Yorkshire was known to have added her own codicil to the poem:

To follow thee, I’m not content

Until I know just where thee went.

By the next century, transi or cadaver tombs became quite popular in England. The effigy in such a tomb shows the human body in some state of decay. The skull shown on the cover of my book is taken from one of my husband’s photos of a transi tomb in Exeter Cathedral, while the photo shown immediately below has me looking at a transi tomb in Tewksbury Abbey.

Plague and death greet the reader of Memento Mori in the prologue to my story. Laston, the squire of the knight Sir Alban, Lady Apollonia’s fourth son, is returning from a crusade of the Teutonic Knights that he and his master had joined. He is trying to find Apollonia to inform her of the death of her son from the plague and bring her what little remains of her son were possible in 1392. Eventually, he finds her in Gloucester and one important aspect of my story tells how Apollonia deals with her loss.

The Lady decides, in Memento Mori, to construct a fitting memorial for the remains of her son. In writing this story, I was guided by a fourteenth century tomb in Exeter Cathedral, shown below, as my inspiration for how Apollonia wished her son’s tomb to be designed. This badly damaged Exeter example displays an effigy of a knight with his squire on the left and his horse, on the right.

Please join me in December when I will continue speaking of other aspects of medieval life described in Memento Mori.