The fourth chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: Basic Essentials. It deals with various aspects of everyday life, especially things which did not operate in 14th century England as they do today. These include the languages spoken and how people expressed dates and measured time. It also included topics such as units of measurement, how people were identified, the manners and politeness etiquette of the time, how people greeted others, what was used for money, what shopping was like, what were the prices of things, and what work and wages were like.

The fourth chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: Basic Essentials. It deals with various aspects of everyday life, especially things which did not operate in 14th century England as they do today. These include the languages spoken and how people expressed dates and measured time. It also included topics such as units of measurement, how people were identified, the manners and politeness etiquette of the time, how people greeted others, what was used for money, what shopping was like, what were the prices of things, and what work and wages were like.

The 14th century was a time of great change in language in England. At its beginning, French was the language used by all nobility and royalty. It was the language of the royal court and of the legal system and of literature. The peasants spoke early forms of English, but those from far apart Northumberland and Devon could hardly understand each other. In Celtic Cornwall, Cornish was preferred.

However, King Edward III, who reigned for half a century from 1327 to 1377, spoke English and influenced its use in new situations by mid-century both for making pleas in the law courts and in his speeches opening parliament. He popularized spoken English among the nobility, and it was being used for literature by the time of my novels at the end of the century. This was the period of Geoffrey Chaucer as well as Julian of Norwich, perhaps the first female author in the English language.

The other thing I would like to say about language in England is that how people speak is greatly influenced by their class. Someone like Margaret Thatcher took speech lessons so that she would sound more like the queen than the grocer’s daughter which she was. This difference in speech was very important to her in the 20th century. It has been so for a long time. Prior to the 14th century, the nobility and the peasants spoke entirely different languages, as mentioned above. I chose to use a mild dialect to distinguish the common folk in Lady Apollonia’s time with the proper English used by the Lady and many in her affinity.

Another basic essential in life is the calendar or how we date things. It was complicated in the 14th century. First, the English often used a regnal calendar which dated events from the beginning of each monarch’s reign. I have occasionally used this device in my writing. Even for those who used Anno Domini, there was no agreement on when the year started. This was a problem throughout Europe, so that travellers could actually go back a year if they happened to visit a town which had not yet started its new year. January 1, March 25 (Lady Day), and September 29 (Michaelmas) were used as the start of the year in various parts of England.

Measuring time was quite different in the 14th century. We use clocks, watches, and other time devices which divide the day into 24 hours of equal length, but clocks were new and rare in Lady Apollonia’s time. The medieval clock in Wells Cathedral in England’s West Country dates to as early as 1386, while the astronomical clock at Exeter Cathedral did not appear until a century after Apollonia’s time. Without a way to divide each day into 24 equal hours, how did people keep time? The answer is that they used sun-dials to divide the daylight into 12 equal parts. The twelve parts of summer daylight were very long compared to a dozen divisions of the short summer nights. The reverse was true in the winter. Since England is further north than the continental United States, these differences were more pronounced there than they would be in America.

Before the United Kingdom became metric, most Americans viewed the system of English units as being irregular, but even English units such as the pound were not standard throughout medieval England. In Devon, the pound was 18 ounces rather than the 16 ounces in much of medieval England and modern America. The Devon bushel was ten gallons, not the eight used in the rest of the country. A Yorkshire mile was 2428 yards compared with the 1760 yards standardized since 1593 c.e.

Another area of change in 14th century was how people were assigned names. One name was sufficient in 1300 for most peasants. They only needed to be identified by the locals. English people began to move around more by mid-century due to changes in economic conditions and the great plague. Hence, identification required more than a simple name. It had to include where you came from, what you did as a worker, or some indication of your status. Note that Lady Apollonia of Aust gives her identity as a noble woman and someone identified with a specific place, Aust. In her case, the heraldry of a red heart encircled by a vine of English ivy was also part of her identity.

We may think of medieval society as dirty, violent, and uncouth, but there were situations in which manners and politeness were important. The nobility, including royalty, expected others to behave in an appropriate, respectful manner. A person did not enter the home or private space of an equal or superior without permission. Weapons were checked with a gatekeeper or handed to one’s host. English dramas that involve royalty often show how one acts in the presence of a monarch. Kneeling is expected at appropriate times. One does not speak unless spoken to by the monarch, nor does one turn his back to the monarch when leaving. Even sitting is not permitted until given permission.

Manners and politeness are intertwined. We might be surprised that politeness was expected even at the table when eating. Hand washing before eating was expected as was cutting bread, rather than just tearing off a piece as is often depicted in dramas set in the period. Some things depended on gender. Women were not expected to swear or get drunk when away from home. Men did not kiss each other except as a sign of peace, as an acknowledgement of fealty or service, or as a ceremonial act. When greeting people, especially for the first time, you were expected not to be overfriendly or too cold.

Towns and cities had markets which operated at least weekly and fairs that came annually. The latter often were scheduled in a three-day period centered on some saint’s feast day. Both retail and wholesale shopping could occur. Markets and fairs were augmented by specialist shops. A shopper would go to a shoemaker to buy a pair of shoes, but the shoemaker might have purchased the leather for the shoes wholesale in some market.

The markets in smaller towns could not regularly carry many specialized items daily. To rectify this problem, itinerant merchants such as furriers would travel to various nearby towns on their market days to offer specialized items such as the furs of a particular animal. Most major towns and cities had a guild merchant, a trade organization controlling who could and who could not trade at markets. Buyers who were cheated by a merchant could sometimes receive justice by complaining immediately to these trade organization.

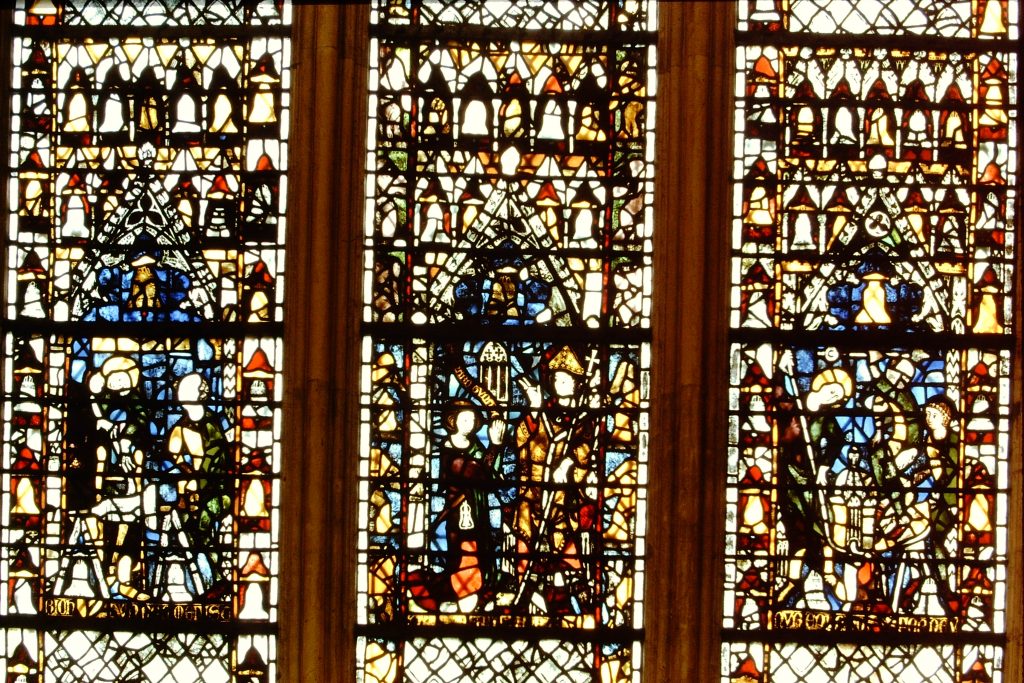

Guilds for various trades were often powerful and wealthy organizations. The picture at the top of this posting shows the Bell-Founder’s window in York Minister dating from the early 14th century. Guilds often sponsored stained glass windows in medieval churches both in England and on the continent.

Money was usually exchanged in small coins. Pennies were most common, but there also were half-pennies and farthings which were worth a quarter penny. There were some larger coins, such as a groat (worth four old pence) and a noble (worth 80 old pence), but none of these was worth as much as a pound Sterling. Inflation in 14th century England was almost non-existent, so prices at the end of the century were much the same as at the beginning. There were temporary fluctuations however in times of crises such as the Great Plague or in years when there was a crop failure. The plague, for example caused a temporary deflation because there was a surplus of food due to all the human deaths.

Obtaining a good job often required some money to get started. It cost something to become an apprentice in a craft. To join a guild, one had to be a freeman, that is not a slave or serf, and then pay a fee to the guild. Wages of a few pence per day varied by craft and season of the year and did tend to improve during the century. A master mason or master carpenter earned much more, equivalent to an educated professional person such as a lawyer or physician. At the other end of the income scale were household staff who did not earn much, even in royal households.

Early in this blog posting, I mentioned Mother Julian of Norwich. I am appending a recent article I wrote about her as a postscript which you may find interesting:

Mother Julian of Norwich

In writing fictional medieval mysteries, I use a number of real people of the fourteenth century in my books, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Arundel, Kings Richard II and Henry IV. One of those real people who play a role in my stories was an anchoress in Norwich, the county town of Norfolk. Very little is known about her life, but she was thought to have been born about 1342 and is thought to have lived into her seventies (c. 1429) as she was the beneficiary of several wills, the latest of these is dated 1416.

Although a very religious person, it cannot be said that she was a nun or solitary in 1373, because during her near-death illness, her mother and other companions were with her and the parish priest who administered the last rites to her was accompanied by a child. She makes a modest disclaimer of her literary ability by calling herself “unlettered”, but that may have simply meant to say that she was unskilled in church Latin. We know from her writings that she is a well-educated person who quotes from the Bible.

The book for which she is known as the first female writer in the English language, Revelations of Divine Love, is her very personal description of a vision she experienced after her near-death illness. Her writing style is spontaneous and vivid with an eye for detail, and she is precise, whether dealing with instruction or spirituality. Her English is a blend of East Anglian and Northern dialects.

In the 21st century U. S. A., we have little awareness of the religious solitary life in which one withdraws from the world to give oneself to a life of prayer, but in the middle ages, the solitary life was respected and encouraged for men and for women. Hermits were male solitaries with considerable freedom of movement doing good works. A recluse was a man or woman shut away from social living but remaining within the community. A male anchorite or female anchoress were those who were enclosed in their anchor hold or residence, frequently attached to a church building. Every medieval town in England had some of these solitary peoples who were authorized by the church.

The mass or religious service of an anchoress’s enclosure was grim as we look at it today. It was essentially the Mass of the dead at the end of which a procession was made from the church to the hermit’s cell. Once entered, however, the person was literally thought to be in his or her tomb, dead to the world and only alive to God. The anchoress that I refer to in my stories was called Julian of Norwich, but that was probably not her real name. She took her name from the Church of Saint Julian to which her anchor hold was attached.

In addition to her book, we know something of Julian from one of her visitors, another somewhat bizarre fourteenth century female who had her personal story of pilgrim’s travels written down for her, Margery Kempe, who describes her visit: “Much was the holy dalliance that the anchoress and this creature(Margery) had by communing in the love of our Lord Jesus Christ the many days that they were together.”

For me, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe seem to overcome the limited potential available to medieval women. Each of them came to make extraordinary choices in their personal lives which expressed their purpose in life. It was not only that their writings were in Chaucer’s English, in the case of my heroine, the Lady Apollonia of Aust, they were models for a medieval female character who achieved individuality in a world where women were mere servants of men.

Tags: Chaucer's England, historical fiction, medieval mysteries