In recent months, I have been using the chapter titles of an excellent book on English medieval life to discuss various aspects of how people of the time lived. The eleventh and last chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: “What to Do”. One might describe it in contemporary language as what people did for entertainment in their leisure time. To my surprise, much of what they did in their spare time was similar to, and often laid the groundwork for, activities I remember as a child and young person before the advent of television, computers, the internet, and iPhones.

In recent months, I have been using the chapter titles of an excellent book on English medieval life to discuss various aspects of how people of the time lived. The eleventh and last chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: “What to Do”. One might describe it in contemporary language as what people did for entertainment in their leisure time. To my surprise, much of what they did in their spare time was similar to, and often laid the groundwork for, activities I remember as a child and young person before the advent of television, computers, the internet, and iPhones.

Barbara Tuchman, in her book A Distant Mirror has compared the 14th century with the 20th, and the similarities are striking. Wars and disease took a heavy toll in both centuries, yet despite these calamities, or maybe because of them, people were often exuberant about life. For example, music and dancing were important in both centuries. There was less ambient noise in the 14th century, well before the industrial revolution, and people listened carefully and loved music when they had the opportunity to hear it.

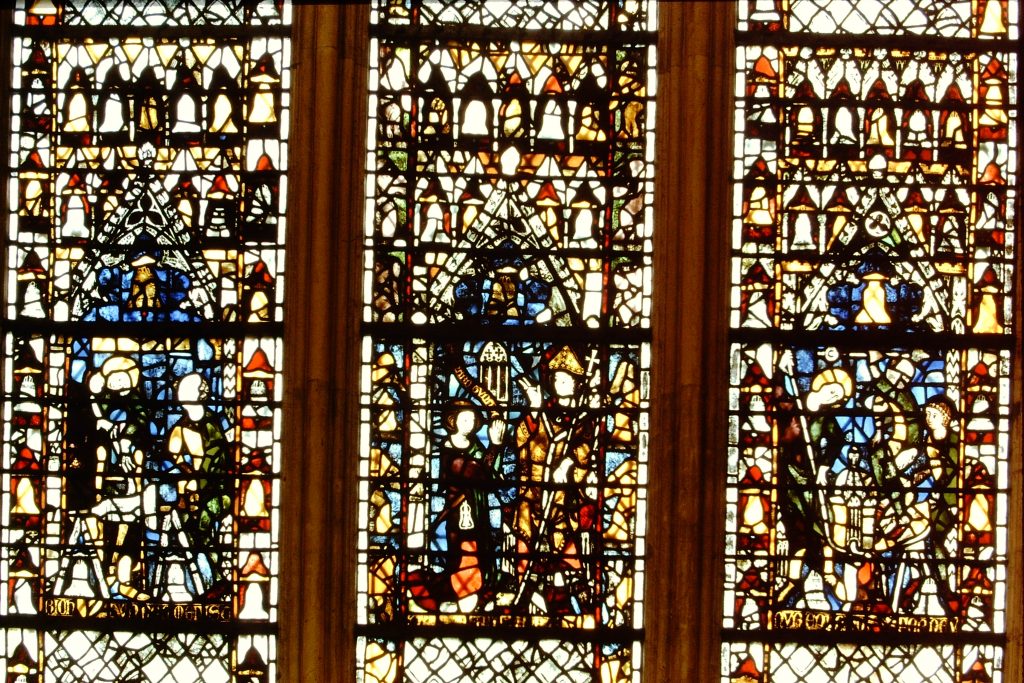

Early versions of many modern musical instruments existed in the 14th century. I have written in previous postings about the wonderful Minstrels Gallery in Exeter Cathedral where medieval angels, carved in stone, are playing instruments of the 14th century. One can easily recognize a violin before it developed into the instrument we know today. There is a portative pipe organ which an angel holds in her arms. There are early woodwind instruments such as the double-reed shawm and medieval string instruments such as the gittern and citole as well as a harp. Two trumpets represent the brass family of instruments, but only the mouthpiece has survived for one of them. The picture above shows an angel playing a harp, and two others playing trumpets, the left one being the broken one.

People of the 14th century also liked to dance whenever they had the opportunity. Something called carolling was popular, but I don’t mean the singing of Christmas carols. In the middle ages, the caroller would stand inside a ring of dancers and sing the verse of a song which often was secular. Then, the dancers would join in singing the chorus before the caroller moved on to the next verse.

Plays were another popular form of entertainment. Miracle or mystery plays were performed regularly in cities, including Exeter and Worcester where my second and sixth books are set. These plays were usually based on biblical stories or on the lives of the saints. They were often performed on wagons that could be moved about the city centre. Morality plays were just beginning at the end of the 14th century but became very popular in the 15th and 16th centuries. Such plays were a kind of drama with personified abstract qualities, such as Pride or Covetousness as the main characters and presenting a lesson about good conduct and character.

Jousting was a tilting activity performed by two knights and enjoyed by many people who watched the match. It was a refinement of mass charges by many knights in earlier centuries. That approach to warfare had become impractical in the 14th century with the English use of the longbow, so a jousting contest became an entertainment that many could enjoy.

Hunting was an important activity for the nobility but wasn’t part of the entertainment of the rest of society. It was very expensive as well as being exclusive. Hawking, on the other hand was popular with many people, including the nobility. It, too, could be quite expensive, but the more exotic birds were reserved for royalty and noblemen.

Many children’s games were similar to contemporary ones that I played in my younger days. Various kinds of brutal contests between men and animals were popular. For example, bear-baiting in which a bear would be tormented or worried by other animals such as dogs was regarded as entertainment. Such abuse of animals for show was also applied to other animals such as bulls or cocks.

There were early forms of some games that we know today such as soccer football, bowling, field hockey, and tennis. Archery was perhaps the foremost sport because Englishmen were required by law to develop skills with the longbow. I mention this in my recent book, Usurper’s Curse, when the teenager, Waldef, takes up archery. Indoor games included the use of dice, coins, and board games such as checkers and chess. Playing cards, however, though becoming popular in France did not arrive in England until the 15th century.

Pilgrimage during the middle ages was in an activity category by itself. Many people went on pilgrimages to religious sites, in England, throughout Europe, and to Jerusalem, for a variety of personal reasons. Such people play a role in some of my stories. Phyllis of Bath in Plague of a Green Man has been on several major pilgrimages just like Chaucer’s Wife of Bath on whom she is based. Similarly, Robert Kenwood who appears in both King Richard’s Sword and in Usurper’s Curse was returning from a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela at the beginning of the former story. My character of Robert Kenwood was inspired by the 20th century find in Worcester Cathedral of a medieval body, known as the Worcester Pilgrim.

Books and storytelling were important to 14th century Englishmen, but the books available to them before the printing press were manuscripts which were rare and valuable. When they were accessible, they were often read aloud to groups of people. A popular fictional work in the 14th was called a romance. Poetry was also widely popular. Well known poets of the period were John Gower, William Langland, and the Gawain Poet whose name we don’t know. The 14th century was the century when English as a language began to be used in literature. The most famous poet was Geoffrey Chaucer, some of whose characters have greatly influenced my stories. Another important writer of the time was Mother Julian of Norwich, the first woman to write in English. Julian’s writing influenced my heroine, the Lady Apollonia, in my first book, Effigy of the Cloven Hoof.

What people did in their spare time in the 14th century may not have been identical with the activities of people of the 20th century, but one can see that many interests of the period shared some similarities, and frequently laid the groundwork for modern leisure pursuits.