Trying to summarize my experiences in Washington, DC, so far this summer, despite the short time that I have been here, is a somewhat challenging task. I have learned a great deal of new information, whether it be at work or while experiencing the city. Much of this information I have taken at face value, trusting in the knowledge of those more experienced with DC than myself. But as I have begun to acclimate to DC life and met more and more people, I am beginning to process my early experiences and make my own connections. And in some cases, I am starting to challenge some of my initial assumptions and things I have been told.

My first few weeks at Internews were fairly quiet. I met with Jon, my supervisor, was given a desk space and laptop, was introduced to my coworkers who were in the office that day, and reviewed and started working on some of the projects that had been planned for me. But the rest of the office was preparing for RightsCon. All the members of the Global Technology Team, my team, were attending the annual conference that was being held in Tunisia the following week. The conference focuses on the intersection of human rights and technology with an international scope, and is attended well by representatives from Internews and other organizations like it.

To illuminate, Internews is an international independent media development nonprofit organization. Internews works with journalists, activists, and other organizations around the world. In many of these countries, the government, other actors, or external factors may exert control on what appears in the news or how accessible this information is to the public. Much of Internews is divided into regional teams, serving Latin America and the Caribbean, Eastern Europe and Eurasia, the Middle East and North Africa, and so on. My team, the Global Tech Team, works outside these traditional regional teams to provide more specialized services. We plan and implement projects that provide technical support to organizations in the countries we serve. This is critical because these citizens in these countries are more and more reliant on technology as it becomes more widely accessible.

So, as my Team prepared for their conference, work started a little slow. But, after they returned, we dove right in to work. I have weekly meetings with specific teams, check-ins with my supervisor, and optional meetings with other project groups with my own team or other teams. In the meantime, I work on programming solutions to the projects I have been given, to support finished, ongoing, and potential future projects.

More specifically, I am working to revise and restructure their SAFETAG program documentation, a program that provides resources to perform digital safety audits for media organizations. (These audits include asking questions like: how are we storing our interview notes, collected data, etc? Is it encrypted for our journalists’ safety? Is our website or application vulnerable to attack from bad actors (groups that we report on ranging from criminal organizations to our own government)? In addition to this, I have been working on analyzing internet usage metrics to determine when governments are shutting down, throttling, or censoring the internet in their country. And I have a few more projects I might work on depending on how far along we get during the summer.

But just in working on these projects, I have learned a lot. I have learned how many communities around the world struggle with internet shutdowns or censorship. I have learned that even in developing countries, more and more business is conducted relying on internet connection or smartphone usage. And I have learned that countries that shutdown internet do so knowing it will cost their economy millions of dollars, directly affecting the livelihood of most of their citizens. And yet they continue to do so, to silence activists, to attempt to curb protests or demonstrations, or to keep the rest of the world in the dark about a coup d’état or human rights violations carried out by the government or military.

I have learned that although we all want to help these countries with their difficulties, getting funding for projects is competitive. I have learned that international development can be messy, and that organizations like Internews have to be careful to think about consequences of running programs so that they do not escalate or make situations in certain countries worse.

I would say the most challenging and frustrating aspect of my work is that our organization addresses problems I have never had to deal with, in communities that I have never interacted with. And yet, I find myself spurred on because I am constantly reminded of the freedoms that I enjoy. The promise of the internet, of integration into an ever more connected world, has often been heralded as the Great Equalizer. But still there are obstacles to communication and access to information, and often to those in most need. And I am glad that I get to play a small part in trying to make it more equitable.

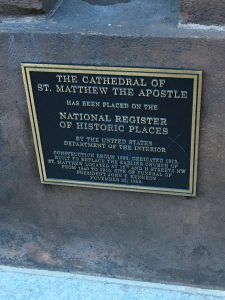

Beyond that, I have done the typical DC things. I visited the monuments, some the of the museums, walked past the White House. I have tried new restaurants and new kinds of food, gone to public events like Jazz in the Park and Jazzfest on the wharf, and visited Arlington National Cemetery. I am hoping to catch a few games of professional tennis at the Citi Open this coming weekend, if I can get tickets. One of the most interesting things I learned about DC, and on of the things I like the most, is that there is a great deal of work that is done here that is not done anywhere else. That includes the obvious ones like federal government and related fields like public policy, lobbying, government contract work, and international development, like Internews.

There are some drawbacks to having unique and interesting work, though. It gives one a whole lot to think about when they are trying to decide whether they want to stay in DC after their summer fellowship ends…