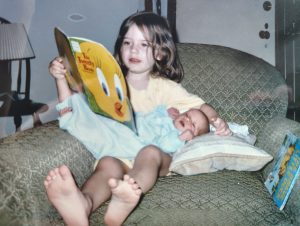

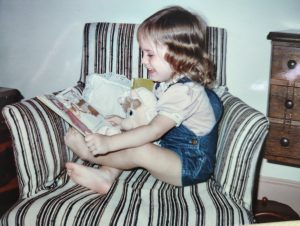

As a young toddler–bright-eyed and babbling happily–I loved few things more than a good story. I was known to pad into a room, book in tow, while clamoring for what I cheerfully called a “once-a ponce-a.” So many children’s books and fairy tales, after all, take narrative flight with the well-worn opening line, “Once upon a time…” Hence, my half-comprehending shorthand. Slightly older and intent to share (force?) my love of story on my younger sister, I would solemnly intone the beginning for her the same way (to the doubtless mirth of any nearby adult). Nevertheless, “once-a ponce-a” rapidly became a family expression.

Perhaps I could channel this tale from childhood into destiny, invariably paving the way to my status as a justified book nerd with a doctorate in literature. A little tidy, but not without some merit.

Actually, though, this early anecdote has been on my mind recently for another reason: as a testament to the enduring power of story; a reminder of the propulsive force of narratives as avenues to deeper truths sometimes difficult to recognize in our workaday lives. As humans, we make sense of the world and the people around us through the stories we tell ourselves and others. Whether we pause to acknowledge this instinctual process or not, our story-making still wields tremendous power for how we show up and move through the world.

Knowing this, we can lean into the power of stories as a way of making sense of complex experiences and realities in our adult lives. By being more self-conscious in this process, perhaps we can also tell each other and ourselves truer stories to counteract the dishonesty that pervades our current culture.

Moreover, narrative agency is crucial to our vocational discernment and our educational journeys, and lately I’ve been particularly delighted to find deeper, common cause around this idea with friends and colleagues from a variety of disciplines and perspectives doing some amazing work on our campus. Dr. Reva Johnson in the College of Engineering has been training in, and drawing on, “story-driven learning” to help students more intentionally scaffold connections between scientific and narrative modes of understanding, between their personal and professional experiences and identities. In newly reimagined VUE courses, students’ topics of study meet active, experiential learning in fieldwork–whether they might be gardening, or volunteering with a local non-profit, or cooking, or exploring historic campus spaces, or observing peer-led organizations as sites of learning-in-action. Their reflections around these experiences can become avenues into deeper self-awareness about the ways they show up in the world, exploring the nuance of leadership and service. Meanwhile, in the honors college, Dr. Amanda Ruud marshals lively ideas from deep discussion about justice, community, and “the good life” to facilitate first-years’ inspiring creation of an original piece of musical theatre–a dramatic account of the conversations and ideas they’ve been wrestling with, making sense of the complex in story and song. It’s all really quite remarkable, and these are but a few potent examples of intentional story-making as avenues to deeper understanding and work in the world happening right here at Valpo.

At the risk of completely nerding out on everyone reading this reflection (sorry, not sorry), some of the most influential work around narrative identity and agency coming out of the social sciences hailed from none other than a Valpo alum, Dr. Dan McAdams ‘76 (Psychology and Humanities, CC Scholar), now professor emeritus at Northwestern University. McAdams pioneered a field urging scholarly study of our own narrative constructions and their power to shape who we are and who we become. (You can read more about his work here.)

Our story-telling matters, and it does real work, both in the world and in the ways we understand our own showing up and agency in that beautiful, broken, ever-evolving world. As a former colleague regularly reminded me–citing novelist Tim O’Brien’s powerful and true line: “Stories can save us.” Of course they can. One need look no further than the New Testament parables.

Less than a week ago, I had the privilege to observe this power anew as current Valpo senior Natalya Reister offered a poignant reflection at Morning Prayer, bearing witness to the ways our stories to ourselves can make and save us. (If you didn’t get a chance to be there in person, I would urge you to check out her moving remarks here on the Valpo Chapel YouTube channel.) Natalya recounts the overwhelm so many of us can attest to at the start of a new chapter in our lives, recalling herself as a first-year student huddled in the Lankenau chapel unable to see the bigger story she is part of and sometimes slowly, painfully helping to write. In her reflection, she casts herself back to this time, addressing a younger version of herself with tenderness and a deeper sensibility of things coming together in ways she cannot at that time see but must learn to implicitly trust:

“[R]ight now, you’re sitting in the Lankenau chapel, and you feel alone. And that’s okay too. It is a part of your journey and God isn’t going to give up on you. Our lives are a mural of experiences and stories. At the moment, though, you are living and focusing on just a small little corner. You don’t yet see the artistry in the narratives God is painting. So take a breath and slow down. The sorrows and the hurts are real, but they are not the end of the story.”

Would that we all would take that sort of tender care, choosing to narrate gently and truthfully from our own empowered voices… while also never forgetting that we are not, blessedly, the end of the story. We offer our “once-a ponce-a,” now and always, in a transcendent narrative frame.

–Dr. Anna Stewart, Director of the Institute for Leadership and Service