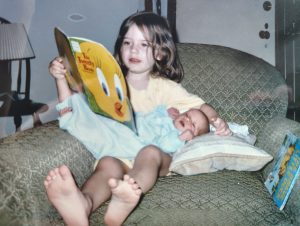

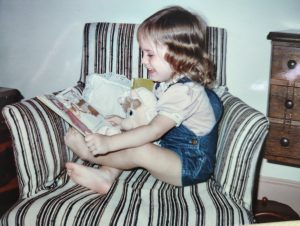

As a young toddler–bright-eyed and babbling happily–I loved few things more than a good story. I was known to pad into a room, book in tow, while clamoring for what I cheerfully called a “once-a ponce-a.” So many children’s books and fairy tales, after all, take narrative flight with the well-worn opening line, “Once upon a time…” Hence, my half-comprehending shorthand. Slightly older and intent to share (force?) my love of story on my younger sister, I would solemnly intone the beginning for her the same way (to the doubtless mirth of any nearby adult). Nevertheless, “once-a ponce-a” rapidly became a family expression.

Perhaps I could channel this tale from childhood into destiny, invariably paving the way to my status as a justified book nerd with a doctorate in literature. A little tidy, but not without some merit.

Actually, though, this early anecdote has been on my mind recently for another reason: as a testament to the enduring power of story; a reminder of the propulsive force of narratives as avenues to deeper truths sometimes difficult to recognize in our workaday lives. As humans, we make sense of the world and the people around us through the stories we tell ourselves and others. Whether we pause to acknowledge this instinctual process or not, our story-making still wields tremendous power for how we show up and move through the world.

Knowing this, we can lean into the power of stories as a way of making sense of complex experiences and realities in our adult lives. By being more self-conscious in this process, perhaps we can also tell each other and ourselves truer stories to counteract the dishonesty that pervades our current culture.

Moreover, narrative agency is crucial to our vocational discernment and our educational journeys, and lately I’ve been particularly delighted to find deeper, common cause around this idea with friends and colleagues from a variety of disciplines and perspectives doing some amazing work on our campus. Dr. Reva Johnson in the College of Engineering has been training in, and drawing on, “story-driven learning” to help students more intentionally scaffold connections between scientific and narrative modes of understanding, between their personal and professional experiences and identities. In newly reimagined VUE courses, students’ topics of study meet active, experiential learning in fieldwork–whether they might be gardening, or volunteering with a local non-profit, or cooking, or exploring historic campus spaces, or observing peer-led organizations as sites of learning-in-action. Their reflections around these experiences can become avenues into deeper self-awareness about the ways they show up in the world, exploring the nuance of leadership and service. Meanwhile, in the honors college, Dr. Amanda Ruud marshals lively ideas from deep discussion about justice, community, and “the good life” to facilitate first-years’ inspiring creation of an original piece of musical theatre–a dramatic account of the conversations and ideas they’ve been wrestling with, making sense of the complex in story and song. It’s all really quite remarkable, and these are but a few potent examples of intentional story-making as avenues to deeper understanding and work in the world happening right here at Valpo.

At the risk of completely nerding out on everyone reading this reflection (sorry, not sorry), some of the most influential work around narrative identity and agency coming out of the social sciences hailed from none other than a Valpo alum, Dr. Dan McAdams ‘76 (Psychology and Humanities, CC Scholar), now professor emeritus at Northwestern University. McAdams pioneered a field urging scholarly study of our own narrative constructions and their power to shape who we are and who we become. (You can read more about his work here.)

Our story-telling matters, and it does real work, both in the world and in the ways we understand our own showing up and agency in that beautiful, broken, ever-evolving world. As a former colleague regularly reminded me–citing novelist Tim O’Brien’s powerful and true line: “Stories can save us.” Of course they can. One need look no further than the New Testament parables.

Less than a week ago, I had the privilege to observe this power anew as current Valpo senior Natalya Reister offered a poignant reflection at Morning Prayer, bearing witness to the ways our stories to ourselves can make and save us. (If you didn’t get a chance to be there in person, I would urge you to check out her moving remarks here on the Valpo Chapel YouTube channel.) Natalya recounts the overwhelm so many of us can attest to at the start of a new chapter in our lives, recalling herself as a first-year student huddled in the Lankenau chapel unable to see the bigger story she is part of and sometimes slowly, painfully helping to write. In her reflection, she casts herself back to this time, addressing a younger version of herself with tenderness and a deeper sensibility of things coming together in ways she cannot at that time see but must learn to implicitly trust:

“[R]ight now, you’re sitting in the Lankenau chapel, and you feel alone. And that’s okay too. It is a part of your journey and God isn’t going to give up on you. Our lives are a mural of experiences and stories. At the moment, though, you are living and focusing on just a small little corner. You don’t yet see the artistry in the narratives God is painting. So take a breath and slow down. The sorrows and the hurts are real, but they are not the end of the story.”

Would that we all would take that sort of tender care, choosing to narrate gently and truthfully from our own empowered voices… while also never forgetting that we are not, blessedly, the end of the story. We offer our “once-a ponce-a,” now and always, in a transcendent narrative frame.

–Dr. Anna Stewart, Director of the Institute for Leadership and Service

I would like to invite you into a journaling activity this week. We at the Institute for Leadership and Service like to promote reflection. We think of it as a muscle we can exercise. You know, how strong muscles are just kind of “nice to have” until one day when you need to move a couch or pick up a child, and then those muscles become absolutely necessary. Similarly, reflection may seem superfluous, until the day we kind of just need to know what we think about a subject.

I would like to invite you into a journaling activity this week. We at the Institute for Leadership and Service like to promote reflection. We think of it as a muscle we can exercise. You know, how strong muscles are just kind of “nice to have” until one day when you need to move a couch or pick up a child, and then those muscles become absolutely necessary. Similarly, reflection may seem superfluous, until the day we kind of just need to know what we think about a subject. The longer I’m at Valpo, the more I’ve come to appreciate the rituals that bookend our academic year. (Twenty year-old me would not have predicted this.) I enjoy donning those odd, medieval robes, hood, and tam to line up and process down the magnificently long aisle of the Chapel in August, organ music swelling the usually thick, humid air as we welcome new students and the return of the academic calendar’s cycle. This year the cool weather granted us all a reprieve at Convocation–merciful when you’re attired in a polyester and velvet concoction.

The longer I’m at Valpo, the more I’ve come to appreciate the rituals that bookend our academic year. (Twenty year-old me would not have predicted this.) I enjoy donning those odd, medieval robes, hood, and tam to line up and process down the magnificently long aisle of the Chapel in August, organ music swelling the usually thick, humid air as we welcome new students and the return of the academic calendar’s cycle. This year the cool weather granted us all a reprieve at Convocation–merciful when you’re attired in a polyester and velvet concoction.

Over the course of this summer and my internship at Erie House, one thing has became ever more clear to me each time I wake up and head to work: any number of individually insignificant factors can decide whether or not it’ll feel like a good day. For example, it could be cloudy but not raining, my bus is on time, and I have an extra minute to grab coffee before I clock in. That’s already a good day. Just as much, if it’s raining without an umbrella, both of my bus rides get delayed, and I have to show up twenty minutes late, that’s kind of a rough start.

Over the course of this summer and my internship at Erie House, one thing has became ever more clear to me each time I wake up and head to work: any number of individually insignificant factors can decide whether or not it’ll feel like a good day. For example, it could be cloudy but not raining, my bus is on time, and I have an extra minute to grab coffee before I clock in. That’s already a good day. Just as much, if it’s raining without an umbrella, both of my bus rides get delayed, and I have to show up twenty minutes late, that’s kind of a rough start.

Today is my last day of my CAPS summer fellowship at Heartland Alliance. I look around the office. It’s quiet, a normal Friday morning as people mostly elect to work remotely before the weekend. Regardless, while everyone goes about their day, I sit here reflecting on some of the things I have learned this summer about both the work I have gotten to be a part of in refugee resettlement and as part of a non-profit at large in Chicago, IL.

Today is my last day of my CAPS summer fellowship at Heartland Alliance. I look around the office. It’s quiet, a normal Friday morning as people mostly elect to work remotely before the weekend. Regardless, while everyone goes about their day, I sit here reflecting on some of the things I have learned this summer about both the work I have gotten to be a part of in refugee resettlement and as part of a non-profit at large in Chicago, IL.

‘I don’t know.’: the response that never feels good enough. Whether it is an answer to what you want, why you started, or what you plan for the future, few leave a conversation satisfied when you say ‘I don’t know’. But I, personally, don’t know a lot of things. I am a very indecisive person; I like to do a lot of things, and I don’t mind doing a lot of things, so, while some people might call me a people pleaser, I would say I’m just really adaptable. I want what others want because I would be content with either.

‘I don’t know.’: the response that never feels good enough. Whether it is an answer to what you want, why you started, or what you plan for the future, few leave a conversation satisfied when you say ‘I don’t know’. But I, personally, don’t know a lot of things. I am a very indecisive person; I like to do a lot of things, and I don’t mind doing a lot of things, so, while some people might call me a people pleaser, I would say I’m just really adaptable. I want what others want because I would be content with either. A lot of people think that I am a shy person. But really, I am just an anxious person, and that results in me thinking and rethinking through any possible implications and consequences of any actions or words before doing or saying them. And when I do not pre-think through them, I will post-think through them afterwards. Or both, which can really slow an interaction. Shockingly enough, that kind of hesitation comes across as shy.

A lot of people think that I am a shy person. But really, I am just an anxious person, and that results in me thinking and rethinking through any possible implications and consequences of any actions or words before doing or saying them. And when I do not pre-think through them, I will post-think through them afterwards. Or both, which can really slow an interaction. Shockingly enough, that kind of hesitation comes across as shy. Just like at Valpo, the Grünewald Guild has a walking labyrinth outside, just beyond their central building and right next to the river. Anyone can use it at any point of the day, or night even. I actually heard from someone that they went out to walk it at night and stargaze. We use it during our final Vespers service of each program week too; to meditate on all the things we’ve learned from the week, to center ourselves and find a few minutes of peace and quiet inside our busy bodies.

Just like at Valpo, the Grünewald Guild has a walking labyrinth outside, just beyond their central building and right next to the river. Anyone can use it at any point of the day, or night even. I actually heard from someone that they went out to walk it at night and stargaze. We use it during our final Vespers service of each program week too; to meditate on all the things we’ve learned from the week, to center ourselves and find a few minutes of peace and quiet inside our busy bodies. As I’m finishing out my internship here at the Guild with only one week left, I’m looking back on the memories I’ve made with the people and the land around me. Some experiences have opened new doors for me that I’d like to keep open as I come back to Valpo. Others have shown me interesting perspectives and walks of life that add to my understanding of the world and how I engage with it. I think I’ll be visiting our labyrinth at Valpo a lot more often next year.

As I’m finishing out my internship here at the Guild with only one week left, I’m looking back on the memories I’ve made with the people and the land around me. Some experiences have opened new doors for me that I’d like to keep open as I come back to Valpo. Others have shown me interesting perspectives and walks of life that add to my understanding of the world and how I engage with it. I think I’ll be visiting our labyrinth at Valpo a lot more often next year. As of late July, I have served as a Communications Intern at Grünewald Guild in Leavenworth, WA for two months as part of my placement as a member of the CAPS Fellows Program. Through working in this position, I have exponentially grown to further refine my vision for my vocation as I approach the final year of my academic career at Valparaiso University. The mission of the guild is highlighted through the three core values of art, faith, and community and, since I am a Music and English major, I initially thought I would gravitate my attention mostly towards the value of art during my time here. Surprisingly, that was not that case and I started to primarily focus upon the aspect of community involvement and how it uniquely manifests itself at this non-profit organization. By nature, I have more of an introverted demeanor and it often takes me a bit of time to feel comfortable with expressing myself in a new environment. Interestingly enough, I did not feel as timid as I typically do during a transitional period of my life, and I think that lack of apprehension I felt is due to the Guild deliberately being a welcoming and community-oriented environment by its very design.

As of late July, I have served as a Communications Intern at Grünewald Guild in Leavenworth, WA for two months as part of my placement as a member of the CAPS Fellows Program. Through working in this position, I have exponentially grown to further refine my vision for my vocation as I approach the final year of my academic career at Valparaiso University. The mission of the guild is highlighted through the three core values of art, faith, and community and, since I am a Music and English major, I initially thought I would gravitate my attention mostly towards the value of art during my time here. Surprisingly, that was not that case and I started to primarily focus upon the aspect of community involvement and how it uniquely manifests itself at this non-profit organization. By nature, I have more of an introverted demeanor and it often takes me a bit of time to feel comfortable with expressing myself in a new environment. Interestingly enough, I did not feel as timid as I typically do during a transitional period of my life, and I think that lack of apprehension I felt is due to the Guild deliberately being a welcoming and community-oriented environment by its very design.

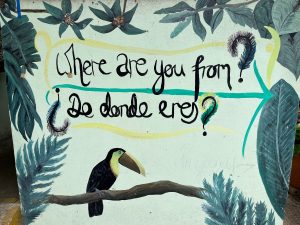

Reconnecting with my high school viola teacher after three years brought up her valid question of, “Any updates with what you want to do with your life?” When I replied, “Well, I want to apply for programs to study or teach in another country for a year… Then possibly grad school for something ‘international’…” we both had to pause and laugh; nothing had changed in the three years since we’d last talked. I still didn’t have a set plan.

Reconnecting with my high school viola teacher after three years brought up her valid question of, “Any updates with what you want to do with your life?” When I replied, “Well, I want to apply for programs to study or teach in another country for a year… Then possibly grad school for something ‘international’…” we both had to pause and laugh; nothing had changed in the three years since we’d last talked. I still didn’t have a set plan. As I near the end of my time at Jacob’s Ladder, I am once again given the chance to reflect on the different experiences and opportunities I have been given this summer. Among all the different opportunities that I have had at my placement, the ones that stick out the most to me are those where I could attend other meetings/events in the community. All of the events that I attended gave me the chance to meet new people, have meaningful discussions with others, and learn new information. These events helped me get out of my comfort zone and learn new information that I will carry with me far beyond my time at Jacob’s Ladder.

As I near the end of my time at Jacob’s Ladder, I am once again given the chance to reflect on the different experiences and opportunities I have been given this summer. Among all the different opportunities that I have had at my placement, the ones that stick out the most to me are those where I could attend other meetings/events in the community. All of the events that I attended gave me the chance to meet new people, have meaningful discussions with others, and learn new information. These events helped me get out of my comfort zone and learn new information that I will carry with me far beyond my time at Jacob’s Ladder.  At the beginning of June, I moved to a town I had never visited, to live in a house I had never seen, and to work with people I had only spoken to over Zoom. My family dropped me off, and once I had all of my things arranged, I sat on the bed and had a strange but very familiar feeling wash over me: What do I do now? I had the whole night ahead of me, but everyone I know and everything I do was scattered everywhere but here. The empty span of time ahead of me felt dizzying. So, I just sat there in the what-now feeling, thinking. I began to think about why this feeling was so familiar to me, and I thought of all of the other transitions I have had like this throughout my whole life: from the five times I moved as a kid, to the move into college, to my trip studying abroad, I began to realize that this is all old hat to me. I have done this before, and sure enough, I have done this again.

At the beginning of June, I moved to a town I had never visited, to live in a house I had never seen, and to work with people I had only spoken to over Zoom. My family dropped me off, and once I had all of my things arranged, I sat on the bed and had a strange but very familiar feeling wash over me: What do I do now? I had the whole night ahead of me, but everyone I know and everything I do was scattered everywhere but here. The empty span of time ahead of me felt dizzying. So, I just sat there in the what-now feeling, thinking. I began to think about why this feeling was so familiar to me, and I thought of all of the other transitions I have had like this throughout my whole life: from the five times I moved as a kid, to the move into college, to my trip studying abroad, I began to realize that this is all old hat to me. I have done this before, and sure enough, I have done this again.  As my internship draws to a close, I’m faced with the same question that I begin the internship with. Why am I working with an environmental non-profit, what difference could I ever make?

As my internship draws to a close, I’m faced with the same question that I begin the internship with. Why am I working with an environmental non-profit, what difference could I ever make?

My opinions do matter, and it is possible to voice them loudly. Like a small rock making waves in a pond, a grass growing in the middle of a cracked sidewalk, a bee pollinating the vegetables in a neighborhood garden. My voice is not as small as I have been made to believe.

My opinions do matter, and it is possible to voice them loudly. Like a small rock making waves in a pond, a grass growing in the middle of a cracked sidewalk, a bee pollinating the vegetables in a neighborhood garden. My voice is not as small as I have been made to believe. As I sit down to write this blog post, one realization crosses my mind. It is the realization that time keeps marching forward, and that is especially true when it comes to summer and my placement. As of the first week of July, I have officially hit the halfway mark of my duties serving Opportunity Enterprises and Camp Lakeside. The phrases “Time flies when you’re having fun” and “You never truly appreciate what you have until it’s gone” perfectly define and encompass what this experience has been. As I look back at what I have accomplished, a lot of it hasn’t felt as actual work. This is not only true for myself, but also for the campers and staff that I interact with on a daily basis. While much of my job is done behind the scenes, I also have many opportunities throughout the week to interact with campers in a way that I still fulfill my duties as a researcher for the camp and OE as a whole.

As I sit down to write this blog post, one realization crosses my mind. It is the realization that time keeps marching forward, and that is especially true when it comes to summer and my placement. As of the first week of July, I have officially hit the halfway mark of my duties serving Opportunity Enterprises and Camp Lakeside. The phrases “Time flies when you’re having fun” and “You never truly appreciate what you have until it’s gone” perfectly define and encompass what this experience has been. As I look back at what I have accomplished, a lot of it hasn’t felt as actual work. This is not only true for myself, but also for the campers and staff that I interact with on a daily basis. While much of my job is done behind the scenes, I also have many opportunities throughout the week to interact with campers in a way that I still fulfill my duties as a researcher for the camp and OE as a whole.

We often hear the phrase “don’t make excuses, make improvements”. For many, this may be a difficult thing to be told – this kind of statement misses and overlooks the individual nuances and circumstances of the situation we find ourselves in. But despite these challenges, we now find ourselves forced to continue on with no acknowledgement of them.

We often hear the phrase “don’t make excuses, make improvements”. For many, this may be a difficult thing to be told – this kind of statement misses and overlooks the individual nuances and circumstances of the situation we find ourselves in. But despite these challenges, we now find ourselves forced to continue on with no acknowledgement of them. When I take a step back now and consider Heartland’s broader role in its community, it falls in some sense along the lines of this exact idea, providing solutions in all kinds of forms in housing, employment assistance, vocational English language training and even trauma assistance. The team here can only think in these terms (solutions, that is); when people’s livelihoods depend on you, you have no choice.

When I take a step back now and consider Heartland’s broader role in its community, it falls in some sense along the lines of this exact idea, providing solutions in all kinds of forms in housing, employment assistance, vocational English language training and even trauma assistance. The team here can only think in these terms (solutions, that is); when people’s livelihoods depend on you, you have no choice.