CoCoDA stressed to me and other travelers on the Friends of CoCoDA Tour that we must be culturally humble when we travel to different communities in Central America. We must understand that we are probably not accustomed to how people live in underdeveloped countries. If we are not aware of this, our interactions may have be negative without us actually realizing it. After returning, I have realized it is almost more difficult to be culturally humble in the United States. That is an incomplete conclusion. I was in Central America (El Salvador and Nicaragua) for 2 weeks and have traveled to Haiti and Guatemala with WAVES for 2 weeks total before this summer. Cultural humility is not easy abroad, but it is simple when I only have to be there for a short amount of time. I have spent the rest of my life in the U.S., and cultural humility is still an intense learning process.

The ethics of service are strikingly similar from country to country. Working with Central American employees and serving people in developing countries is almost the exact same. In the last week of my internship, CoCoDA sent me to Bloomington, Indiana to shadow the founder and president of Whole Sun Designs, a solar panel installation company. I participated in 8 site visits between the president and clients that were pre-installation and close-out meetings. The men I worked with were intentional and visionary about the details of installing the next few projects, planning projects four weeks in advance, and directing the company in the direction they want it to go. The president had high, though reasonable expectations for everyone. I knew CoCoDA functioned like this as a non-profit serving under-resourced people in Central America. I watched Whole Sun Designs do this as a for-profit, and it changed how I thought a business could operate and still reap amazing results. Successful businesses do not have to choose which clients to hold in contempt or treat employees with partiality.

I was surprised at how the president and employees wove integrity and fairness to each other and their customers as integral to the company’s operation. Our conversations in the site visits, which were usually at people’s houses, reminded me of when I evaluated solar panel systems in El Cacao, Nicaragua. We were just as respectful to their homes and ensured we understood how they wanted to use their system. For example, the president could recommend taking a tree down to maximize sunlight on one part of the roof. He would not follow through with it if the client did not want it. People also showed us awesome parts of their property that they had developed. They were proud of it just like homeowners in Central America were proud of their home development. The only difference between serving clients of Whole Sun Designs and CoCoDA is who could afford the system and who could not. That single difference introduces a running lists of nuances that lead can lead to poor service in developing countries for those who do not continuously collaborate with their clients.

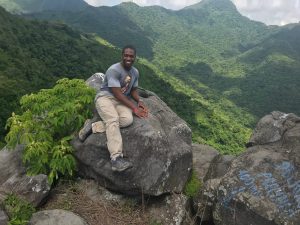

Indiana itself has flooded me with varying levels of emotions that are common nuances in life in life in this country. I know how Indiana has treated black people in the past, so I had to be mindful of that everywhere I went. The threat was not as serious in Indianapolis or Bloomington, but I could not get it out of my mind. I stayed at the house of the president of Whole Sun Designs for two nights. I could not believe that we drove for 20 minutes through forest to get to his house. I am from Chicago. I have buildings and streetlights, not open land and trees. The hills reminded me of Nicaragua’s landscape more than anything else! The president’s roommates were very welcoming people; so was everyone else I met. I have been to many cities in the U.S., yet cultural humility seems more complicated to exercise here than abroad. That is probably because I live here and encounter different cultures on a regular basis rather than touring other countries for a week at a time.

I have not yet gotten into the nitty-gritty of commitment to community development, or business development. I am thankful for this summer internship because I have been exposed to methods of doing both ethically. I will not have to shift into my career thinking there are only avenues to success that are cut-throat. Pragmatism, realism, and respect will be enough.