The ninth chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: Health and Hygiene. It describes the developments of these topics in 14th century England. As an author, I love writings stories set in medieval England, but my sons tell me that I really wouldn’t have wanted to live in that era because of the awful smells. They are probably right because there certainly were bad odours, and many of these were caused by conditions which affected the health and hygiene of the time.

I moved to Exeter, Devon, with my husband, Lou, in 1988. We moved into a terraced or row house on a hill by the River Exe. There was a medieval stream which ran behind those terraced houses with the name, Shitbrook. That stream did not get its name by accident, so I referred to its unpleasant odour in my second Lady Apollonia Mystery, Plague of a Green Man, which was set in Exeter in 1380.

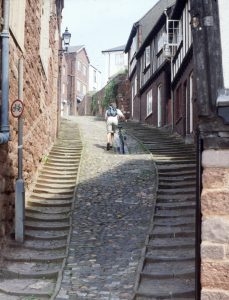

There is also a street in Exeter called Stepcote Hill, which retains its medieval character. It is narrow and steep in its descent to the river. A trough runs down the middle so that, in medieval times, people could throw their garbage and waste into the trough where the next rain would wash it down towards the river. A photograph of that hill is shown on the left. One can only imagine the stench from each of these two examples in medieval Exeter, and such conditions were duplicated throughout communities in England.

There is also a street in Exeter called Stepcote Hill, which retains its medieval character. It is narrow and steep in its descent to the river. A trough runs down the middle so that, in medieval times, people could throw their garbage and waste into the trough where the next rain would wash it down towards the river. A photograph of that hill is shown on the left. One can only imagine the stench from each of these two examples in medieval Exeter, and such conditions were duplicated throughout communities in England.

Sickness was a big problem that was not well understood in the medieval period. Medicine was a bizarre mixture of arcane ritual, cult religion, domestic invention, and a freakshow. Doctors often consulted numerology for guidance or looked to astrology for signs of the zodiac. The latter happened when a doctor of physic was employed by my heroine, Lady Apollonia, when her beloved husband, Edward Aust, returned very ill from London to Exeter in Plague of a Green Man. Medical practice at that time was still very dependent on Galen and Hippocrates who had lived more than one and a half millennia earlier, at which time the humours of choler (yellow bile), phlegm, melancholy (black bile), and blood were considered essential in determining a person’s physical and mental state. Doctors of the period often recommended bleeding the patient to return balance to the body, often to the patient’s detriment.

It is not an exaggeration to say that getting medical help in medieval times may have been more damaging than getting no help at all. In such circumstances, people looked to the church, both to explain sickness as well as to petition for personal help. Many would have agreed with the friends of Job that his misfortunes must have been the result of God’s displeasure for something Job had done.

We are concerned with germs when we think of cleanliness, but germ theory was unknown in medieval times. People were more dependent on how things smelled when judging whether they were clean. They were very concerned with whether they were perceived by their neighbours as being clean. Cleanliness, identity, pride, and respectability were all tied together. Hence, medieval people did try regularly to wash their faces, teeth, hands, feet, body, fingernails, beard, and hair, even if full body bathing was a luxury that many could not do regularly because of expense or because of the availability of clean water.

Diseases, particularly leprosy, tuberculosis, and the plague, were major afflictions in 14th century England. This is not due to differences between medieval and modern hygiene. Rather, the big factors were an inadequate diet for many people, generally poor sanitation, the prevalence of parasites, and the way that living spaces were shared. The latter factor is related to the fact that many major diseases could easily be passed from one human to another living in close proximity, such as in monastic houses or when strangers shared a bed at an inn. Medieval people had no understanding of this aspect of the transmission of disease.

The Great Plague first arrived in England in August 1348, with return visits in 1368-69, 1375, and 1390-91. By 1400, half of those born after 1330 were killed by this disease although no more than third of the population was killed in the initial 1348-49 attack. Lady Apollonia’s son Chad died of the plague in my third novel, Memento Mori, in 1392 while on the continent fighting with the Teutonic Knights.

Leprosy or Hansen’s Disease as we know it in modern times was a major fear for all medieval people, yet leprosy may have been misdiagnoses of what we now call eczema, psoriasis, and lupus. Medieval leprosy in England was in decline by the 14th century, but lepers were shunned as outcasts from their community through a special mass for the living dead. I write of such a situation in Plague of a Green Man.

Tuberculosis was on the rise and, because it could be transmitted by air, tended to be more of a problem in urban areas. Typhoid fever was also a chronic sickness, especially for armies of men massed together in huge numbers. Beyond these diseases, there may have been others in the 14th century which are unknown to us today. Finally, I should mention that natural childbirth was often fatal for the baby and for the mother. All in all, the health and hygiene of the 14th century would have been very difficult for people of the time, and their life expectancies were much shorter than ours.

Tags: Chaucer's England, historical fiction, medieval mysteries