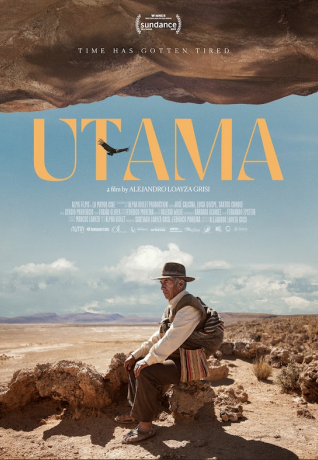

Place Attachment and Cultural Identity in ‘Utama’ (2022)

The communities most impacted by climate change contribute to global warming the least. The damage that developed nations do to these populations is often ignored and as first-world countries continue to advance, they further sever their connection to these vulnerable places. However, the voices of the vulnerable are not entirely lost in the pursuit of progress. Advocates for those impacted by climate change seek various mediums through which to tell these people’s stories, including film, such as Utama (2022), written and directed by Alejandro Loayza Grisi. The protagonists are Virginio and Sisa, an elderly Quechua couple living a simple life in the Altiplano. The landscape is characterized by harsh weather conditions, which oscillate between scorching days and freezing nights, but to the couple, it is their home and until recently, it met all their needs. The film showcases the struggles they face living through an unprecedentedly long drought in the Andean Plateau. Although the story is fiction, it is one of the present; it openly demonstrates the conflicts that many residents of rural Bolivia currently face. It inspires a guiding question: How does the film demonstrate the native people’s sense of place and their struggle to decide whether or not to become climate refugees? Around the world, people are deciding whether to stay and endure a changing environment or become climate refugees at a time when their homes are transforming into increasingly uninhabitable places. Utama couples majestic cinematography of the Altiplano landscape–its main characters’ home–and intergenerational tensions to bring to life the conflict between place attachment and environmental displacement that many individuals who are hurt by climate change must reconcile.

The film takes place in rural Bolivia, particularly Virginio and Sisa’s property, which is situated near a mountain range and overlooking a vast plateau. Their house, shed, and llama pin are minor details in the great expanse, demonstrating the geographical significance of the setting. Place attachment is implicitly linked to geography. Put simply, place attachment refers to an individual’s emotional connection to a particular place and how that place influences one’s thoughts and behaviors (Diener and Hagen 2020, 174). The film’s expansive shots situate the characters as minute details within the vast Altiplano landscape. Conversely, the landscape is integral to the characters’ identities. In Utama, which means “our home,” the Quechua couple’s loyalty to their home demonstrates the deep connection that they have to the Altiplano region of the Andes. According to the director, identity and culture are major themes that the film explores because Bolivians lack a unified national identity (Loayza Grisi 2022; interview by Ben Nicholson). For Virgino and Sisa, their identity emerges from the land: everything about their life, from the simple everyday rituals like fetching water and grazing the llamas, is a product of their location. Only here can they embody those integral aspects of their identities. Viewers quickly learn that the Altiplano, and by extension Virginio and Sisa’s identities, are threatened by global climate change.

The film takes place in rural Bolivia, particularly Virginio and Sisa’s property, which is situated near a mountain range and overlooking a vast plateau. Their house, shed, and llama pin are minor details in the great expanse, demonstrating the geographical significance of the setting. Place attachment is implicitly linked to geography. Put simply, place attachment refers to an individual’s emotional connection to a particular place and how that place influences one’s thoughts and behaviors (Diener and Hagen 2020, 174). The film’s expansive shots situate the characters as minute details within the vast Altiplano landscape. Conversely, the landscape is integral to the characters’ identities. In Utama, which means “our home,” the Quechua couple’s loyalty to their home demonstrates the deep connection that they have to the Altiplano region of the Andes. According to the director, identity and culture are major themes that the film explores because Bolivians lack a unified national identity (Loayza Grisi 2022; interview by Ben Nicholson). For Virgino and Sisa, their identity emerges from the land: everything about their life, from the simple everyday rituals like fetching water and grazing the llamas, is a product of their location. Only here can they embody those integral aspects of their identities. Viewers quickly learn that the Altiplano, and by extension Virginio and Sisa’s identities, are threatened by global climate change.

Intense droughts are just one example of how global warming is changing the environment and consequently the cultural landscape of vulnerable places. In more critical instances, people are forced to leave their homes because conditions turn uninhabitable. The reasons to leave are vast, but as Utama demonstrates, so are the reasons to stay. Those that choose to leave may be considered climate refugees. The term “climate refugee” was first coined in 1985, but due to its complexity, few agencies have taken initiative to clearly identify the phenomenon. In general, a climate refugee describes an individual who is forced to migrate from her home, either temporarily or permanently, due to an environmental disturbance that threatens her lifestyle or wellbeing (Apap 2019, 3). Others consider migration to a larger city as a solution to escape the enduring drought, but the main characters struggle to accept fates as climate refugees because of their connection to the land. When Sisa travels to the anemic river, now the closest water source since the well in their village dried up, the women discuss moving to the city. “Just leave. . .Nobody wants to stay,” they contend over their laundry chores (Loayza Grisi 2022, 00:16:02). But Sisa is unconvinced. Similarly, Virginio is utterly resolute to stay home, even when their grandson, Clever, visits to request that they join him in the city.

The tensions between grandparents and grandson are manifestations of the internal conflict that climate refugees around the world must reconcile: sacrificing place attachment and identity for migration and survival. For the elderly couple–Virginio especially–migration is not an option. Virginio and Sisa’s intense sense of place in the Altiplano keeps them from accepting fates as climate refugees. Although it is a harsh environment, it is the land that they have always called home. Global warming and its negative effects on their homeland are completely out of their control. However, unlike many climate refugees, staying on the land is one of the few choices still within their control, and especially for older generations that have spent their entire lives living this way, such as Virginio and Sisa, they will choose to stay. Aside from identity and lifestyle, preserving their language also influences place attachment. Virginio and Sisa speak to one another in Quechua, a native language of indigenous peoples of South America, but their grandson Clever was not taught. Uprooting these individuals from their native land which promotes their lifestyle removes them from their culture–including their language–and increases the likelihood of its obsolescence and death.

Climate change affects susceptible places in more ways than one. In Utama, the heart of the conflict lies in the elderly couple’s love and loyalty to their home. It is an integral part of their identities, and it is one that they intend to embody until the end, which according to climate scientists, is nearer than one may wish. But there is a glimmer of hope at the end of the film. The love between Virginio and Sisa is reflected in the love and loyalty that the Quechua people have for the land. Even though Virginio dies, Sisa chooses to keep living the life that they know; similarly, as parts of Earth die with climate change, films such as Utama immortalize the culture of a people who may be forced to become climate refugees or otherwise cease to exist altogether. Art is the immortal mode by which these people can preserve the life that they know.

References

- Apap, Joanna. 2019. The concept of ‘climate refugee’: Towards a possible definition. Strasbourg: European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621893/EPRS_BRI(2018)621893_EN.pdf.

- Diener, Alexander C., and Joshua Hagen. 2020. “GEOGRAPHIES OF PLACE ATTACHMENT: A PLACE-BASED MODEL OF MATERIALITY, PERFORMANCE, AND NARRATION.” Geographical Review 112 (1): 171-86. doi:10.1080/00167428.2020.1839899.

- Loayza Grisi, Alejandro. 2022. “Interview: Alejandro Loayza Grisi, dir. Utama.” Interview by Ben Nicholson. CineVue, November 26. https://cine-vue.com/2022/11/interview-alejandro-loayza-grisi-dir-utama.html.

- Loayza Grisi, Alejandro, dir. 2022. Utama. La Paz: Alma Films. https://www.almafilms.net/es/peliculas/utama.