Effigy of the Cloven Hoof is a fictional story set in the time of Geoffrey Chaucer who was the first important writer who wrote in Middle English, the language commonly spoken in England in the 14th century. If you have studied Chaucer, you may have encountered a sample of that language and how it differs from modern English. My challenge, as an author, is to give you a sense of English as it was spoken in those times without writing in Middle English which I and most of my readers are uncomfortable trying to read.

To help my readers have a sense of time and place, I have employed several devices. The text seeks to avoid words which have entered the English language in recent centuries. For example, I thought the word “prithee” would be of my period but then discovered that this abbreviation of “I pray thee” did not originate until the 16th century. Our use of apostrophes in contractions was not widespread 600 years ago. Therefore, Lady Apollonia does not use contractions, nor do those in her affinity who have learned to be well spoken.

Another device is my use of English spellings whenever possible. Many of my readers are American, and my hope is that by using English-only spellings I will draw American readers more easily get into my stories set in 14th century West Country of England. This is obvious with words such as centre/center where the English spell it one way and Americans another. I prefer to use patronise over patronize even though both spellings are permitted in contemporary England because Americans would never use the patronise spelling. I try to encourage my readers to lose themselves in Lady Apollonia’s world of over 600 years ago as they read my stories.

Social class was important in medieval England, and there were differences in how the classes spoke, as is true in our world today. Peasants did not speak like nobles any more than a person with a Cockney accent in 2020 speaks like Queen Elizabeth II. Therefore, I have chosen to create a mild kind of dialect for the common folk in my stories to distinguish them from Lady Apollonia’s type of speech. Hopefully, it is mild enough for easy reading. Contractions do appear in this dialect, a contrast with the speech of the nobility.

Next, let me describe some of the early writers of Middle English. Three of them were contemporaries of my heroine in Effigy of the Cloven Hoof: Geoffrey Chaucer, Mother Julian of Norwich, and the reformer John Wycliffe. Chaucer, especially, has been very helpful to me, particularly because of his characters in The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer is shown above in a 19th century drawing. Unlike most medieval writers, he wrote about English people who came from all walks of life. Members of the nobility are included as well as many church figures and other interesting folk, such as the Wife of Bath. Chaucer’s characterizations provided me contemporary insights into a variety of medieval people but also inspiration for some of the characters in my stories. One of these, Brandan Landow, appears at the very end of Effigy of the Cloven Hoof as a pardoner. He is based on The Pardoner in Canterbury Tales. In all the subsequent books through the seventh, Usurper’s Curse, my pardoner has reappeared and proven to be a character of interest.

Chaucer may be known as the best-known author to write in Middle English, but Mother Julian of Norwich was the first woman to become known as a writer in that language. Her Revelations of Divine Love was given to my heroine to read at a difficult time in her young life. Lady Apollonia found Mother Julian’s writings to be a comfort and inspiration as she struggled to understand her faith following the death of her first husband.

Chaucer may be known as the best-known author to write in Middle English, but Mother Julian of Norwich was the first woman to become known as a writer in that language. Her Revelations of Divine Love was given to my heroine to read at a difficult time in her young life. Lady Apollonia found Mother Julian’s writings to be a comfort and inspiration as she struggled to understand her faith following the death of her first husband.

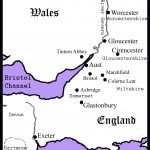

The third writer in Middle English referred to in my stories is John Wycliffe, best known as the Oxford scholar who was first to translate the Bible into English. He is shown in the picture on the left. What is not well known is that in the very years when he was translating the New Testament, Wycliffe was the Prebend of Aust, meaning that the parish church in Aust provided him with some of his income. Such a connection of the real-life Wycliffe with the Lady Apollonia’s home village of Aust inspired me to work him into my story.