Greetings! Please, come with us as we examine some topics which arise in King Richard’s Sword, the sixth book in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries. We begin by looking at the ancient city of Worcester, the setting for the novel. Worcester is located on the east bank of the River Severn, upstream from Gloucester and Aust, other venues for novels set in Lady Apollonia’s West Country. The Severn River was tidal at and beyond Worcester and could be forded at low tide. This crossing was part of an ancient trade route to Wales dating back to Neolithic times and was fortified by the Britons as early as 400 BC. By the late fourteenth century, at the time of my novel, there was a bridge at the fording spot, and a modern replacement of that bridge can be seen in the picture, shown above, looking upstream at the River Severn in Worcester.

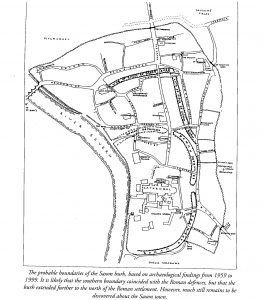

The Romans, who occupied the area by the first century AD, used charcoal from the Forest of Dean to run pottery kilns and produce iron. They also produced salt at this location. Excavations in Worcester have never revealed the kind of municipal buildings which the Romans typically would have built in administrative centers. However, the Romans did build some fortifications to protect their trade and production interests. The map on the left shows where these fortifications were built in the southern portion of what became the Saxon settlement.

The Romans, who occupied the area by the first century AD, used charcoal from the Forest of Dean to run pottery kilns and produce iron. They also produced salt at this location. Excavations in Worcester have never revealed the kind of municipal buildings which the Romans typically would have built in administrative centers. However, the Romans did build some fortifications to protect their trade and production interests. The map on the left shows where these fortifications were built in the southern portion of what became the Saxon settlement.

In the latter part of the first millennium, the Saxons called Worcester by the name Weogorna Ceaster where Weogorna meant people of the winding river with Ceaster being their name for a Roman settlement. Over time, Weogorna Ceaster evolved into Worcester. The walls and gates of the Saxon town are also shown on this map. Some of these gates are mentioned in my story.

We know more about the Anglo-Saxon period than earlier times. The Anglo-Saxons settled in the town in the 7th century. The Wegornan peoples were a sub-tribe of the Hwicce who occupied modern Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, and parts of Wiltshire. In AD 680, the Hwicce picked Weogorna Ceaster for a major fortification as well as the episcopal see of its new bishopric.

Christianity and monastic life already existed in Wegorna Ceaster, when the priory church became the cathedral church of the new diocese, a function it still served at the time in which King Richard’s Sword is set. Several parish churches also existed in the 7th century city, and there was extensive ecclesiastic ownership of lands.

Two Saxon bishops of Worcester achieved sainthood. Oswald was appointed in AD 962 and later also was Archbishop of York, holding that position jointly with his Worcester bishopric. It is he who brought Benedictine Rule to Worcester where the clerics had previously served other orders. Wulfstan was appointed in AD 1062 and continued after the Norman Conquest until his death in 1095. No other Saxon bishop survived after 1072. The crypt of the present cathedral church was built by Wulfstan.

By the 11th century, a bridge was built over the River Severn at Worcester because of the trade route leading to Wales. That bridge was replaced early in the 14th century before I set King Richard’s Sword in Worcester at the end of the century. The Norman conquerors built a castle south of the priory, but nothing remains of it today except Edgar’s Tower which appears in my story. The tower is an entrance to the priory grounds and is shown in the picture below.

Next month, I expect to discuss the history of Worcester from the time of the Norman Conquest. Please join us again as we explore this ancient English city.