Cirencester is the setting for Templar’s Prophecy, the 4th novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. As I discussed in my last posting, the Saxon village within the surviving Roman walls began with a handful but had grown to 350 people by the time of the Domesday Book in 1086. Thereafter, the population grew more rapidly during the medieval period into an important wool town, possibly reaching 2500, though this was reduced by the appearance of the plague in the 14th century. In any event, the town was much smaller than Roman Corinium had been. The medieval population lived only in the northern portion of what had been the Roman town and included homes for various classes: nobility, clergy, merchants, and peasants.

Cirencester is the setting for Templar’s Prophecy, the 4th novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. As I discussed in my last posting, the Saxon village within the surviving Roman walls began with a handful but had grown to 350 people by the time of the Domesday Book in 1086. Thereafter, the population grew more rapidly during the medieval period into an important wool town, possibly reaching 2500, though this was reduced by the appearance of the plague in the 14th century. In any event, the town was much smaller than Roman Corinium had been. The medieval population lived only in the northern portion of what had been the Roman town and included homes for various classes: nobility, clergy, merchants, and peasants.

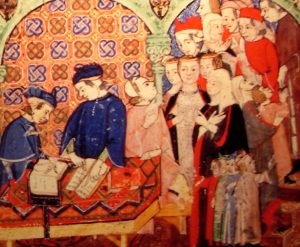

Cirencester is the largest of the towns in the Cotswolds which tourists love to visit today. Cotswold wool was prized throughout Europe in medieval times, and Cirencester became important in the woollen trade by the 13th and 14th centuries, bringing European wool merchants to the town. The woollen trade also introduced banking to its medieval economy, as shown above. The drawing portrays late 14th century bankers handling accounts for merchants.

In Cirencester, wool was woven as well as fulled or cleaned and thickened before being dyed. Dyer Street, where my heroine, Lady Apollonia, lives had been renamed Dyer in the middle of the 13th century from Cheaping Street in recognition of this aspect of the wool business. It is the wool trade which brought Apollonia to Cirencester after the death of her third husband.

Besides being an important centre for the medieval wool trade, Cirencester also served as a more general market town for the region. Its Marketplace at the end of Dyer Street dealt in horses, cattle, goats, bean and pea meal, cheese, butter, fish, salt, alum, iron, lead, tin, brass, linen, and silk. A charter had been granted to the town in 1086 to run a Sunday market, but in 1189 King Richard I sold his manor to Cirencester Abbey for 100 pounds’ sterling and changed the market to a Monday and Friday operation run by the abbey.

A minster church, founded in the 8th or 9th century, became the Augustinian abbey which plays a prominent role in my story, set in 1395. For now, it must be said that the abbey had come to literally dominate the town after 1189. King Richard’s actions in behalf of the abbey caused significant friction between the abbey and the townspeople as to who ran the town’s market. This conflict increased through the years, and I tell of that tension in my story.

For more on Cirencester’s medieval history, click on

http://www.localhistories.org/cirencester.html or on

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cirencester