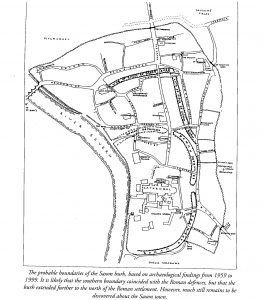

Greetings! Today, we continue to examine some topics which arise in King Richard’s Sword, the sixth book in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries. Our attention is focused on the ancient city of Worcester, the setting for the novel. In my last post I spoke of the development of Worcester from pre-Roman times through the Saxon period. This post will deal with the history of the city from the time of the Norman Conquest in AD 1066.

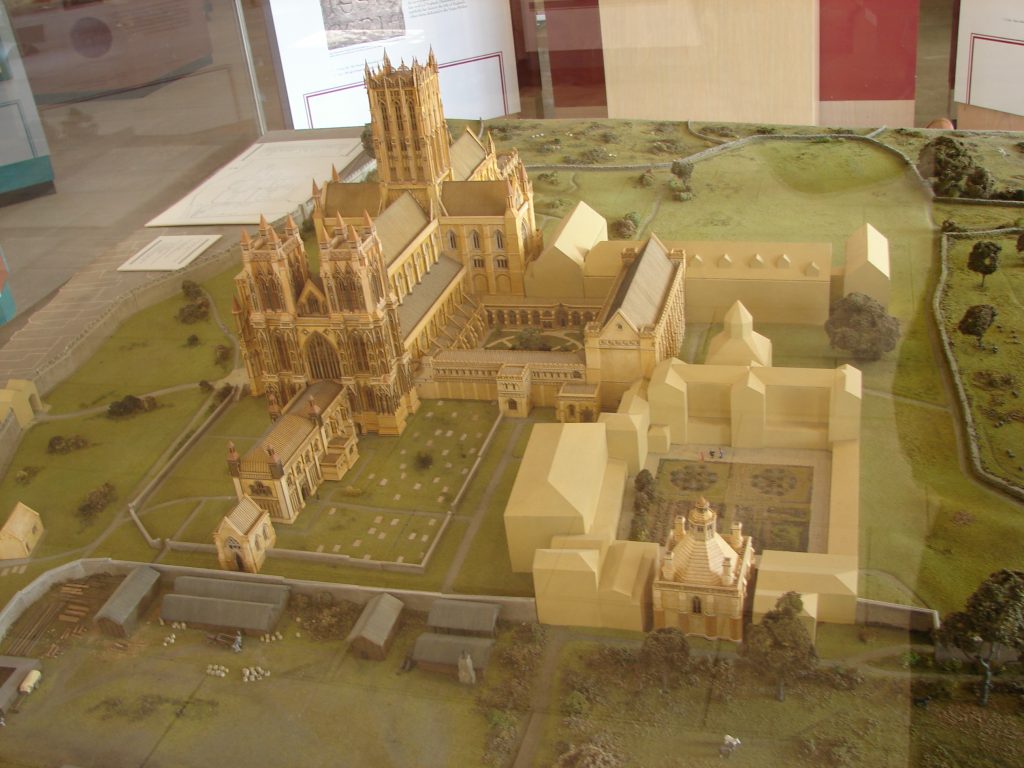

William the Conqueror used the five years after the Conquest to consolidate his power in England. He appointed Urse d’Abetot to be Sheriff of Worcestershire in 1069. Urse immediately began construction of Worcester Castle, just to the south of Worcester Cathedral, with the castle impinging on the cemetery of the monks who formed the cathedral chapter. The picture shown above is of the medieval refectory of the monks that faces what is left of the monks’ cemetery and the castle.

The motte and bailey of this Norman castle overlooked the River Severn at a point where it could be forded at low tide. Wood was used in the castle’s initial construction but was later upgraded to stone. Early in the 13th century, the use of Worcester Castle was reduced to just a goal (jail) which plays a role in King Richard’s Sword.

In my previous blog posting, I mentioned that Saint Wulfstan was the last of the Saxon Bishops to survive in the Norman era. There was much friction between the sheriff and the bishop with the Bishop of Worcester usually coming out on top.

Worcester was a center of religious life with the presence of several monasteries including the Benedictine priory which housed Worcester Cathedral. Saints Oswald and Wulfstan, mentioned in my last posting, each founded a hospital that served the city. Wulfstan’s Hospital shown above was near Sidbury Gate. This gate to the medieval city appears in the prologue to my book.

The hospital itself served also as almshouses and what we now would call a hospice. The present building is up to 800 years old. The exterior of its great hall is shown in the previous picture, while the interior of the hall appears in the picture to the left.

The hospital itself served also as almshouses and what we now would call a hospice. The present building is up to 800 years old. The exterior of its great hall is shown in the previous picture, while the interior of the hall appears in the picture to the left.

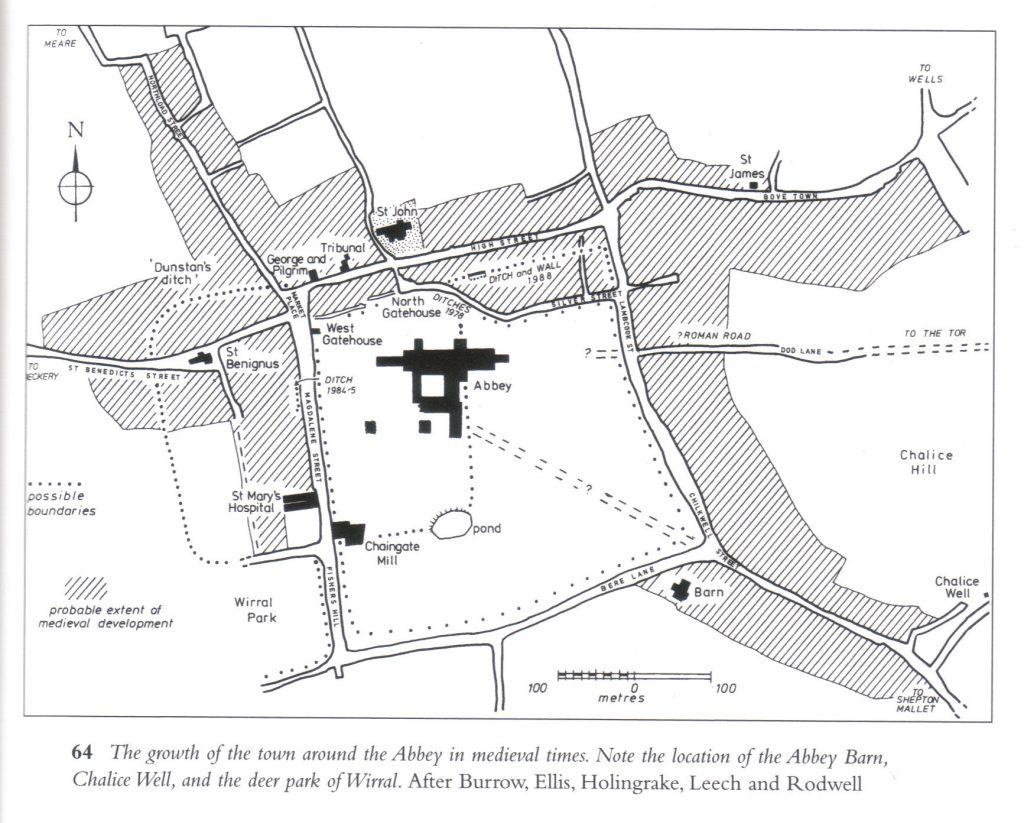

The early 13th century brought a rebuilding of the walls to the growing city and there are many remnants of those walls. A water-filled ditch was just outside the walls except along the River Severn. The picture below shows what is left of the medieval wall along the east side of the city. Much of the medieval wall was levelled in AD 1651 following the battle of Worcester, leaving what you see today.

The medieval walls of the city had many gates. The Water Gate, shown below, along with Frog Gate and Sidbury Gate, mentioned above, were all south of the Cathedral area. Friars’ Gate and Saint Martin’s Gate were important ones on the east side, while Foregate gave access from the north. There were several other openings to the wall along the River Severn, including access to the medieval bridge across the river.

Please join us next time when I will continue the history of Worcester.