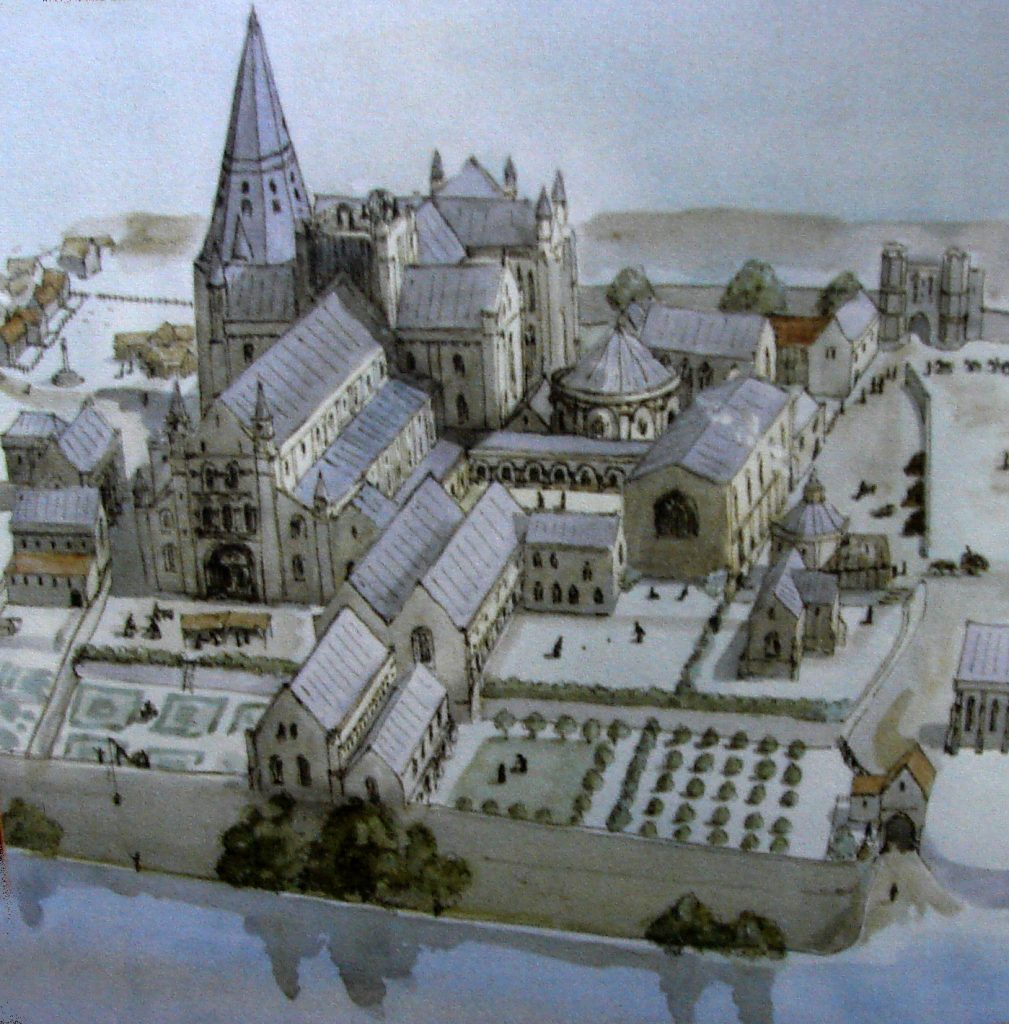

I am currently discussing, in this blog, the medieval church as found in my West Country Medieval Mystery Series, featuring my heroine, the Lady Apollonia of Aust. I began with cathedrals and focused last month on Worcester Cathedral. This month I will speak of Exeter Cathedral, shown in the picture which begins this posting. Unlike Worcester Cathedral, which is a monastic cathedral, Exeter Cathedral is secular, that is, it has always been run by priests called canons who are not monks. It shares this status with many other English cathedrals such as Salisbury, Wells, and York.

I am currently discussing, in this blog, the medieval church as found in my West Country Medieval Mystery Series, featuring my heroine, the Lady Apollonia of Aust. I began with cathedrals and focused last month on Worcester Cathedral. This month I will speak of Exeter Cathedral, shown in the picture which begins this posting. Unlike Worcester Cathedral, which is a monastic cathedral, Exeter Cathedral is secular, that is, it has always been run by priests called canons who are not monks. It shares this status with many other English cathedrals such as Salisbury, Wells, and York.

Plague of a Green Man is set in Exeter, and Exeter Cathedral plays a major role in the story told by that novel. As I mentioned last time, cathedral churches get their name because each holds the throne or “cathedra” of the local diocesan bishop. Exeter’s throne is an enormous medieval wood carving, the tallest in England, reaching almost the 68-foot vaulting overhead. It is shown in the picture on the left. The carver was probably illiterate, but his portrait and that of his wife are carved on the back side of the throne for all to see.

Plague of a Green Man is set in Exeter, and Exeter Cathedral plays a major role in the story told by that novel. As I mentioned last time, cathedral churches get their name because each holds the throne or “cathedra” of the local diocesan bishop. Exeter’s throne is an enormous medieval wood carving, the tallest in England, reaching almost the 68-foot vaulting overhead. It is shown in the picture on the left. The carver was probably illiterate, but his portrait and that of his wife are carved on the back side of the throne for all to see.

Exeter had a Christian church presence in late Roman times and an important minster church in the late centuries of the first millennium. That Anglo-Saxon minster became a cathedral in 1050 when the diocese moved to Exeter from nearby Crediton. Although the minster had originally been a monastic church, the first cathedral church in Exeter was run by secular canons. Leofric became the first Bishop of Exeter. His tomb effigy, which is found in Exeter’s Lady Chapel, is shown below on the right. The new Diocese of Exeter included both Devon and Cornwall.

Work began on the second cathedral church in Exeter in 1117. Its architecture was Norman, and its nave and transepts form the footprint for the present church building. The Norman church was unusual because it had no central tower. Two side towers defined the extent of the transepts. These towers survive in the present Gothic church. The picture at the top shows a Gothic window which was inserted into the north wall of the Norman north tower.

The present cathedral building, started in the 1270’s with the demolition of most of the Norman cathedral, save for the Norman towers and the wall of the nave below the present windows. The new building was in Gothic architecture and is perhaps the best example of the English Decorated Gothic style. That style is maintained throughout the building. Because there is no central tower, the Gothic vaulting that runs from the west to the east of the main building, some 300 feet, is the longest Gothic vaulting in the world. The beautiful tierceron vault is shown in the picture on the left.

The present cathedral building, started in the 1270’s with the demolition of most of the Norman cathedral, save for the Norman towers and the wall of the nave below the present windows. The new building was in Gothic architecture and is perhaps the best example of the English Decorated Gothic style. That style is maintained throughout the building. Because there is no central tower, the Gothic vaulting that runs from the west to the east of the main building, some 300 feet, is the longest Gothic vaulting in the world. The beautiful tierceron vault is shown in the picture on the left.

The Cathedral Green served as the main cemetery of Exeter in medieval times. In modern times people relax on the grass absorbing the sun, as shown in the picture below, but bodies were buried under that lovely grass at the time of Plague of a Green Man, set in 1380. An interesting character in my novel is Eric Aunk whose job was that of pitmaker of the cemetery.

As I have mentioned in earlier posts, Exeter Cathedral is near and dear to my heart since I served as a steward and tour guide there during the various years we lived in Exeter. The picture below shows me thirty years ago with one of the cathedral vergers, sitting together in the bishop’s throne described earlier in this posting.

Next month I will describe another type of cathedral related to one of my stories.