The Augustinian Abbey of Saint Mary in Cirencester plays a major role in Templar’s Prophecy, the fourth book in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. Indeed, the abbey played a major role in Cirencester for over 400 years until the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

The Augustinian Abbey of Saint Mary in Cirencester plays a major role in Templar’s Prophecy, the fourth book in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. Indeed, the abbey played a major role in Cirencester for over 400 years until the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

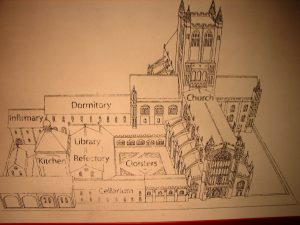

The monastery, as it appears in my story set in 1395, was originally built in the 12th century and included the church and cloister, dormitory, refectory, kitchen, infirmary, cellarium, library, muniment room for storing robes, an inn for poor travellers and pilgrims, and the abbot’s house. The major buildings are shown in the drawing above, which comes from the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. The abbey church was originally built in the Norman style but was largely rebuilt in the 14th century in the Gothic style and included an ambulatory being added around the quire.

The monastery was a community within a town. Abbey grounds were surrounded by walls which had gates. The monks slept in the dormitory, ate in the refectory, held meetings in the chapter house, and went into the church to pray and worship, all buildings within steps of each other facilitated by the cloister which connected them.

The Rule of Augustine was based on charity, poverty, obedience, detachment from the world, the apportionment of labour, the mutual duties of superiors and inferiors, fraternal charity, prayer in common, fasting and abstinence proportionate to the strength of the individual, care of the sick, silence, and reading during meals. The physical layout of the monastery and its buildings were designed to facilitate the monks’ lifestyle based on the Rule.

Between twenty and forty monks, as well as lay-servants and lay-brothers, with the abbot in charge made up the population of the abbey. Frequently the abbot was called away to the royal court, and this was the case at the time of my novel. About that time, the Abbot of Cirencester was upgraded to being a mitred abbot which put him on a par with bishops. His deputy who was in charge in the abbot’s absence was the prior, and my fictitious prior is a main character in my novel.

Individual monks oversaw various functions of abbey life. The infirmarer oversaw the infirmary, the abbey’s version of a hospital or sick bay. The cellarer was the monk in charge of provisions. Keys are often associated with a cellarer because he needed access to the various storage facilities in the monastery as well as farms owned by the abbey. The kitchener worked under the cellarer and managed the kitchen. A chamberlain looked after day-to-day essentials of the monks.