Before I end my current postings on Templar’s Prophecy, the fourth novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series, I want to discuss the tension between the town of Cirencester and the Augustinian Abbey of Saint Mary. This is a topic which I wrote about in several postings in July 2017 and which you can access through the archive link for that month shown on the right below.

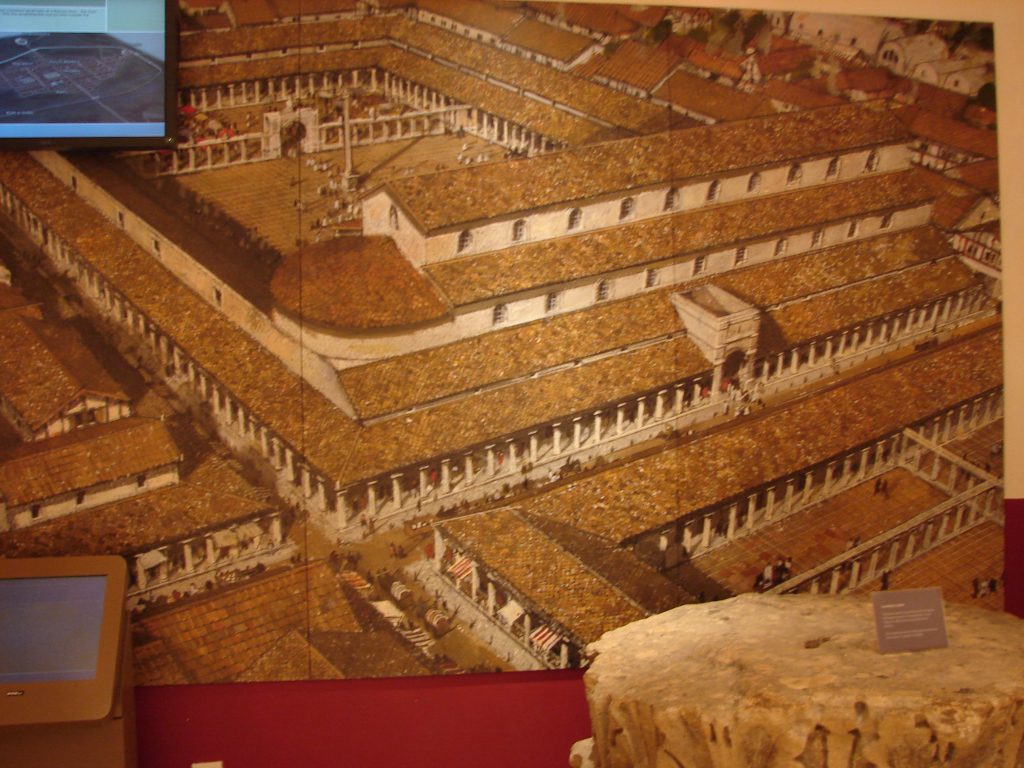

Cirencester Abbey was the largest of the Augustinian abbeys in England and extremely important to the life of the town in which it was located. It was founded in the early 12th century by King Henry I who granted them a charter in 1133 and established their position in the community. I could devote this entire posting to a list of the many endowments both in Cirencester and elsewhere that were awarded to the abbey, but instead, I would like to discuss the tension this caused between the townspeople and the abbey because it plays an important part in my story.

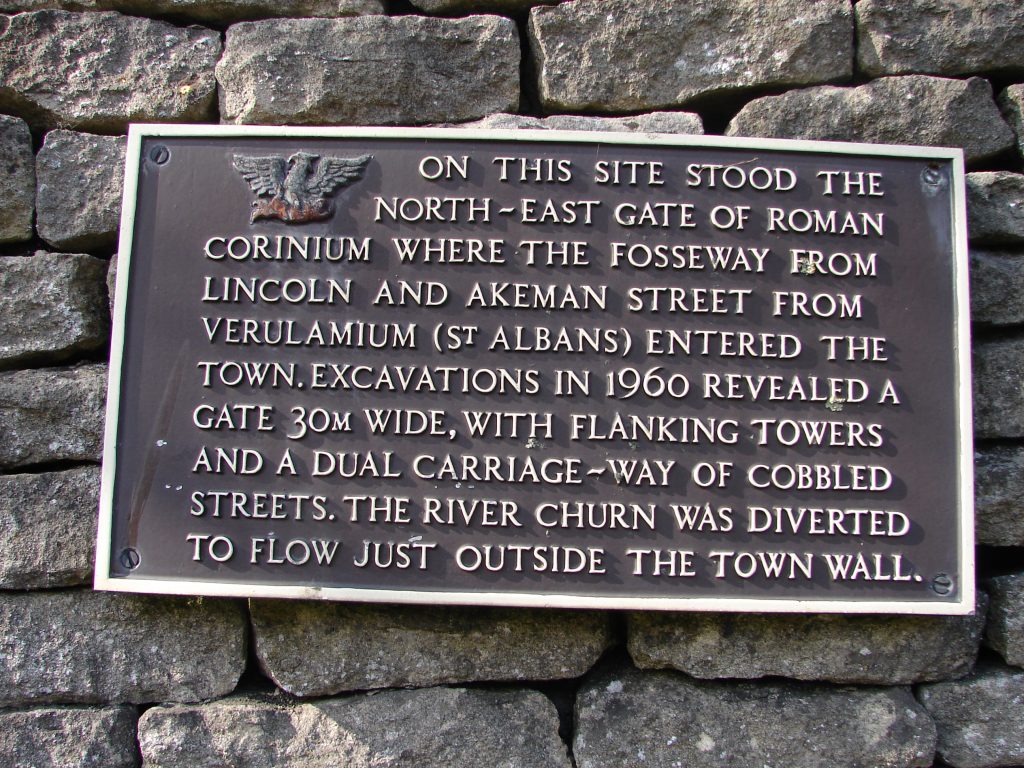

There had been a minster or collegiate church in Cirencester from Saxon times when the town began to repopulate after the Roman withdrawal in the 5th century. This was still the case after the Norman Conquest when the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086 by order of King William the Conqueror. Shortly thereafter, in 1108, the Order of Augustinian Canons was created in England. King Henry I began building the church and the Augustinian monastery in Cirencester in 1117, leading to the appointment of its first abbot in 1131 and the charter in 1133 mentioned above.

There had been a minster or collegiate church in Cirencester from Saxon times when the town began to repopulate after the Roman withdrawal in the 5th century. This was still the case after the Norman Conquest when the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086 by order of King William the Conqueror. Shortly thereafter, in 1108, the Order of Augustinian Canons was created in England. King Henry I began building the church and the Augustinian monastery in Cirencester in 1117, leading to the appointment of its first abbot in 1131 and the charter in 1133 mentioned above.

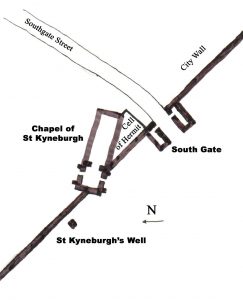

During the reigns of King Henry II and Richard I, the abbey controlled the Manor of Cirencester and with it the whole town. By the early 14th century, the abbey had secured the power of law enforcement usually controlled by the sheriff of the shire and was even awarded its own goal or jail in 1222 by King Henry III. For all practical purposes, the abbey ran the town and grew rich from the valuable wool trade which had developed between the 12th and 14th centuries.

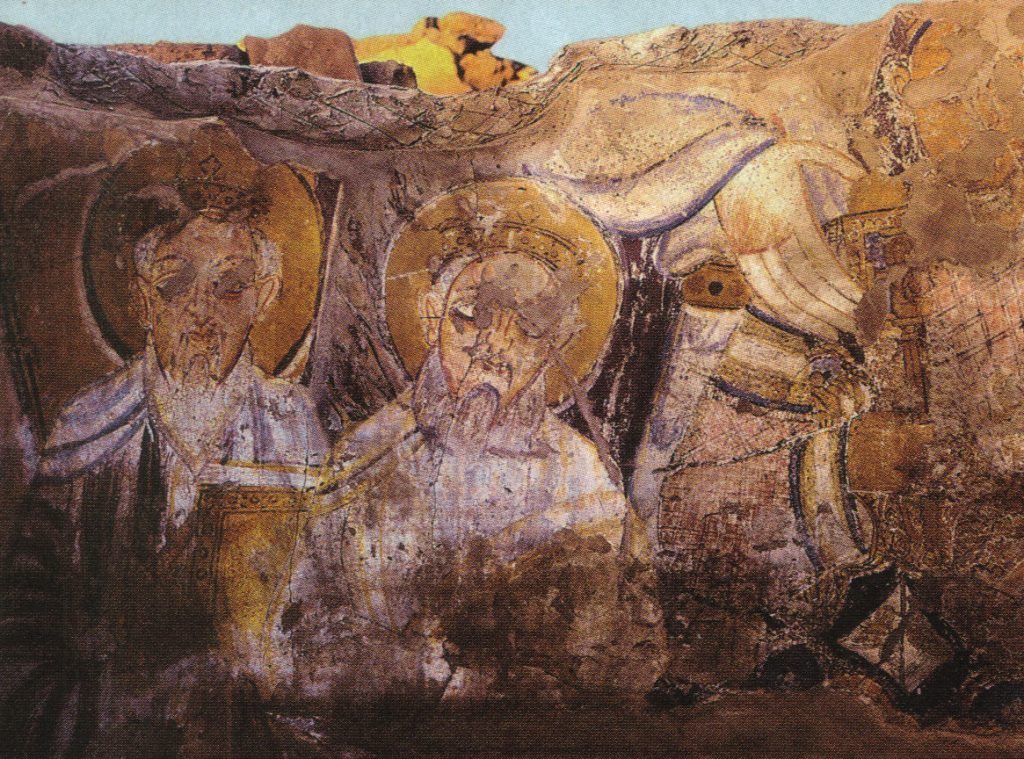

There were three important developments in the 14th century. The first was the rebuilding of the nave of the abbey church which by this time was a magnificent church, dominating the nearby impressive parish church about which I have spoken in recent postings. That parish church is still prominent today in Cirencester. but it is hard to visualize the even more impressive abbey church that was next to it because nothing remains above ground of the abbey church or other adjacent abbey buildings following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII. The Corinium Museum in Cirencester has some objects on display from the abbey church: carved stone faces of a king, a bishop, and a woman, along with medieval floor tiles. Pictures of these objects are scattered throughout this posting.

A second development in the 14th century was the growing friction between the abbey and town. Those townspeople in the growing wool business felt constrained by the control of the abbey. The abbey’s powers in that century were increased by bribes paid by the abbot to the monarch. I have tried to incorporate this tension into my story.

Another development of the 14th century was the townsfolk’s complaint of evil living by some of the monks and other abuses within the abbey. This, too, was a point of tension between the townsfolk and the abbey. Although the plot my story is fiction, I have described some of these abuses into Templar’s Prophecy.

Next time, I will speak of several interesting medieval topics from my fifth book, Joseph of Arimathea’s Prophecy. Please join us then.