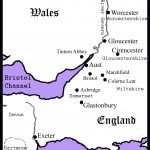

In recent posts, I have been emphasizing some aspects of the fourteenth century Roman Catholic Church which have appeared in my first novel, Effigy of the Cloven Hoof. These have included the presence of clerics resident in the household of my heroine, Lady Apollonia of Aust, the decision of her son Thomas to become a priest, various real English monasteries that appear in the story, the appearance of John Wycliffe, the reformer who actually held the living of Aust, and the Lady’s personal decision as a widow to devote her life to the church as a vowess. The medieval parish church in Axbridge, Somerset, where I placed Apollonia’s son Father Thomas, is shown above.

This post will speak to more general characteristics of the church in medieval life because it was inevitable that the Church must be part of any stories set in the fourteenth century.

First, the medieval Roman Catholic Church was a major temporal power which had great wealth and controlled a significant amount of the land in the Kingdom of England. This may be hard to understand when we consider the relatively small Vatican State (110 acres in Italy) under its control today. The medieval church owned property throughout Europe amounting to a third of all land, but it was not all controlled centrally by the pope as much of it was distributed between countless dioceses and monastic institutions. Although the church expected individuals to contribute a tenth of their incomes in tithes to its coffers, this church property itself was generally tax-exempt. A monastic church tithe barn in Glastonbury, Somerset, built for holding these tithes, is shown below on the left.

While the Church enjoyed a religious monopoly, it did not tolerate challenges, dissent, or protest. People and movements which did not agree with Church doctrine current at the time had been branded as heretical since the earliest days. Such church sponsored programs as the crusade against the Cathars in southern France or the declaration that John Wycliffe, who appears in my book, was condemned as a heretic were expressions of church power.

While the Church enjoyed a religious monopoly, it did not tolerate challenges, dissent, or protest. People and movements which did not agree with Church doctrine current at the time had been branded as heretical since the earliest days. Such church sponsored programs as the crusade against the Cathars in southern France or the declaration that John Wycliffe, who appears in my book, was condemned as a heretic were expressions of church power.

The church in the middle ages was an important part of the everyday life of most people, regardless of class. Worship services were attended regularly, and women especially were known to attend church three to five times daily for prayer in addition to weekly confession and mass. Lady Apollonia and many in her affinity maintained their prayer routine whenever possible. A private chapel within Aust Manor was used daily.

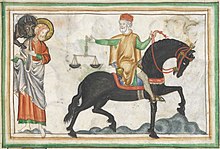

Heaven, hell, and purgatory were truly threatening possibilities to most medieval people. Purgatory was a temporary state where an individual who died might go as punishment for one’s sins and as a place of purification before going to heaven. Many feared that they would have to spend a long period in purgatory or might be sent to hell having committed a mortal sin, and such fears led to one of the great abuses committed by the medieval church: the sale of indulgences.

An indulgence is the full or partial remission of the temporal punishment mentioned above and could be granted by the Catholic Church after the sinner had confessed and received absolution. The Church’s abuse was the sale of counterfeit indulgences by dishonest clerics for their own gain. In the epilogue of Effigy of the Cloven Hoof, I introduce a character, the Pardoner Brandon Landow, who is based upon Geoffrey Chaucer’s character in the Canterbury Tales. Landow plays a significant role in all my later novels.

Two aspects of the medieval church that appear briefly in Effigy of the Cloven Hoof also play a larger role in other of my novels. These are the significance of pilgrimage and relics. For now, I will just say that in this the first book, Apollonia considers going on pilgrimage when she is a teenage widow and that she becomes involved with phony relics in the epilogue. There will be more information about all these topics in future blog posts concerning my other novels.