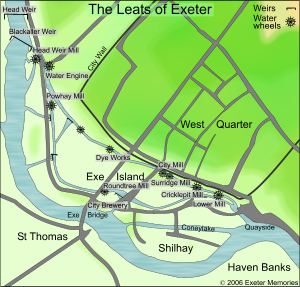

Stepcote Hill and the medieval bridge in Exeter both appear in Plague of a Green Man, the second novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries. Stepcote Hill is one of the oldest streets in Exeter. It gets its name, not from the steps on either side of the street but from its steep descent from the city centre down to the West Gate. This is the path which two of my villains followed in leaving the city. Beyond the West Gate, the medieval bridge was erected in 1238 as the first stone bridge spanning part of Exe Island and the River Exe. It was the third stone bridge in all of England and consisted of 18 arches with a chapel at each end.

Stepcote Hill and the medieval bridge in Exeter both appear in Plague of a Green Man, the second novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mysteries. Stepcote Hill is one of the oldest streets in Exeter. It gets its name, not from the steps on either side of the street but from its steep descent from the city centre down to the West Gate. This is the path which two of my villains followed in leaving the city. Beyond the West Gate, the medieval bridge was erected in 1238 as the first stone bridge spanning part of Exe Island and the River Exe. It was the third stone bridge in all of England and consisted of 18 arches with a chapel at each end.

Stepcote Hill had served since Roman times as the major route into Exeter for strings of pack horses and weary travellers coming from the west. It continued to be used centuries after my story. William of Orange rode up the hill into Exeter with a large force. They were on their way from Brixham, where they landed, to London to take the crown from King James II.

Saint Mary Steps Church stands at the base of the hill on one side, across from it are a couple of 15th century buildings, a bit late for my story. Yet, as you stand by the church and look up the hill, it maintains the feel of a narrow medieval street. The picture above is taken near the bottom of the hill showing Saint Mary Steps Church on the right and ruins of the medieval wall near the West Gate beyond. Interestingly, the ancient jettied house beyond the church was moved to its present location in the 20th century, but it contributes to the historical charm of the location.

The chapel at the west end of the bridge housed the church for Saint Thomas Parish in 1380. My heroine, Lady Apollonia, visited this church, in my story, on her way to visit Phyllis of Bath who lived in that parish. In real life, the chapel was destroyed in a flood in 1384, and thereafter the parish church was built in another location on solid ground.

In the 18th century, the western half of the medieval bridge crossing the main channel of the River Exe was demolished and replaced by a new bridge, but the other half of the medieval bridge stands as a ruin on Exe Island with remnants of Saint Edmunds Church still at its eastern end. The 18th century replacement was a little upstream and more in line with Fore Street than with the West Gate. The 20th century brought three new bridges, now using steel in their construction. The 1905 bridge which replaced the Georgian bridge was demolished in the 1960’s to make way for two one-way bridges which are part of a huge traffic circle.

For more on Stepcote Hill or the Exeter’s medieval bridge, click on

http://www.exetermemories.co.uk and search for these subjects.