Glastonbury in 1397 is the setting for Joseph of Arimathea’s Treasure, the fifth novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. There are many legends about Glastonbury starting from the Roman period but few written records before the Norman Conquest in 1066. What records do exist primarily concern Glastonbury Abbey, and many of those were lost in a fire of 1184 or at the time of the Dissolution by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

Glastonbury in 1397 is the setting for Joseph of Arimathea’s Treasure, the fifth novel in my Lady Apollonia West Country Mystery Series. There are many legends about Glastonbury starting from the Roman period but few written records before the Norman Conquest in 1066. What records do exist primarily concern Glastonbury Abbey, and many of those were lost in a fire of 1184 or at the time of the Dissolution by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

There is written and archaeology evidence concerning Glastonbury Abbey from the seventh century and archaeological evidence concerning Glastonbury Tor, all of which I will discuss in future postings. After the Conquest, there is much written material about both the abbey and the town.

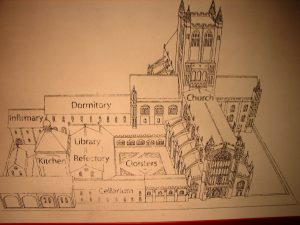

The abbey served as a focal point around which the medieval town grew and towards which the various roads coming into Glastonbury converged. By the 12th century, the abbey grounds formed almost a square around which the town was developing. The High street ran along the north side. On the west was Magdalene Street joining the High Street at the Market Place. Lambcook Street was on the east side. The medieval town grew up on these three sides and extended out in the direction of Wells on the northeast, towards the Chalice Well on the southeast, the village Meare to the northwest, and towards Beckery to the west.

Two parish churches existed at the time of my novel, and both were run by the abbey. Saint John the Baptist on the High Street was the main parish church as it still is today. Saint Benignus, due west of the abbey, served as a chapel under Saint John’s church. In the 17th century, it was renamed Saint Benedict. The picture above looks down Saint Benedict Street towards the church from the area of the Marker Place. Today these two churches are joined with Saint Mary’s in the nearby village of Meare to form one modern parish.

From Saxon times, the town catered to the needs of the abbey and was dependent on its fortunes. In addition to Saint John’s church, there are a couple of buildings today on the High Street that are medieval. One was a Pilgrim’s Inn to serve pilgrims coming to the abbey. In the 19th century it became the George Hotel and is now called the George Hotel and Pilgrim’s Inn. Another is the Tribunal which now houses the Glastonbury Lake Village Museum mentioned in my last post. Each of these was originally built just after my story, but they give an idea of the architecture of the time. There are remnants of medieval almshouses just inside the west entrance to the abbey grounds from Magdalene Street and across that street as a part of Saint Margaret’s Hospital. The abbey tithe barn is just outside the southeast corner of the abbey grounds and now houses the Somerset Rural Life Museum.