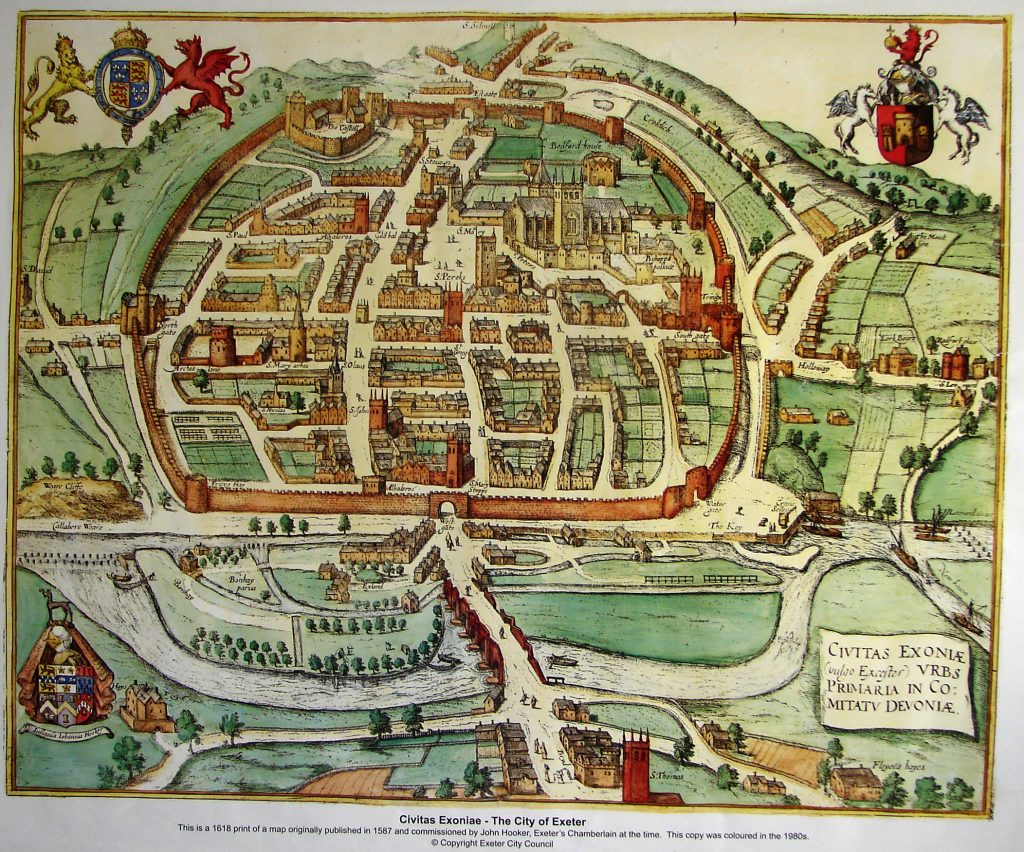

The first chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: The Medieval Landscape. The landscape of England at the time of my novels was essentially rural. Cities in the year 1377 were very small by modern standards. London was the largest city in England at 40,000, followed by York at 12,000. The largest city in the West Country was Bristol at 10,000. Gloucester, the setting for my third novel, Memento Mori, was 16th largest in all of England with 3,700. It had the biggest population among the cities in which I set my stories. Exeter, where the second novel, Plague of a Green Man, is set, had 2,400, as did Worcester, where the sixth novel, King Richard’s Sword, takes place. A drawing of Exeter at the top, done two centuries after my story, shows the city much as it would have been in 1380. Most of the cities were surrounded by walls, as we can see in the drawing of Exeter. These cities were small, but other settings of my novels in the towns of Cirencester and Glastonbury and the village of Aust were smaller still.

The first chapter of Ian Mortimer’s book, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, is entitled: The Medieval Landscape. The landscape of England at the time of my novels was essentially rural. Cities in the year 1377 were very small by modern standards. London was the largest city in England at 40,000, followed by York at 12,000. The largest city in the West Country was Bristol at 10,000. Gloucester, the setting for my third novel, Memento Mori, was 16th largest in all of England with 3,700. It had the biggest population among the cities in which I set my stories. Exeter, where the second novel, Plague of a Green Man, is set, had 2,400, as did Worcester, where the sixth novel, King Richard’s Sword, takes place. A drawing of Exeter at the top, done two centuries after my story, shows the city much as it would have been in 1380. Most of the cities were surrounded by walls, as we can see in the drawing of Exeter. These cities were small, but other settings of my novels in the towns of Cirencester and Glastonbury and the village of Aust were smaller still.

The population figures given above for cities represent the number of permanent residents. These numbers would have been supplemented by visitors passing through these cities or residing temporarily at the many inns which they contained. People were attracted to urban areas from the surrounding countryside every day to take advantage of their regular markets. Clergy, merchants, messengers, king’s officers, judges, clerks, master masons, carpenters, painters, pilgrims, itinerant preachers, and musicians came to cities looking for employment.

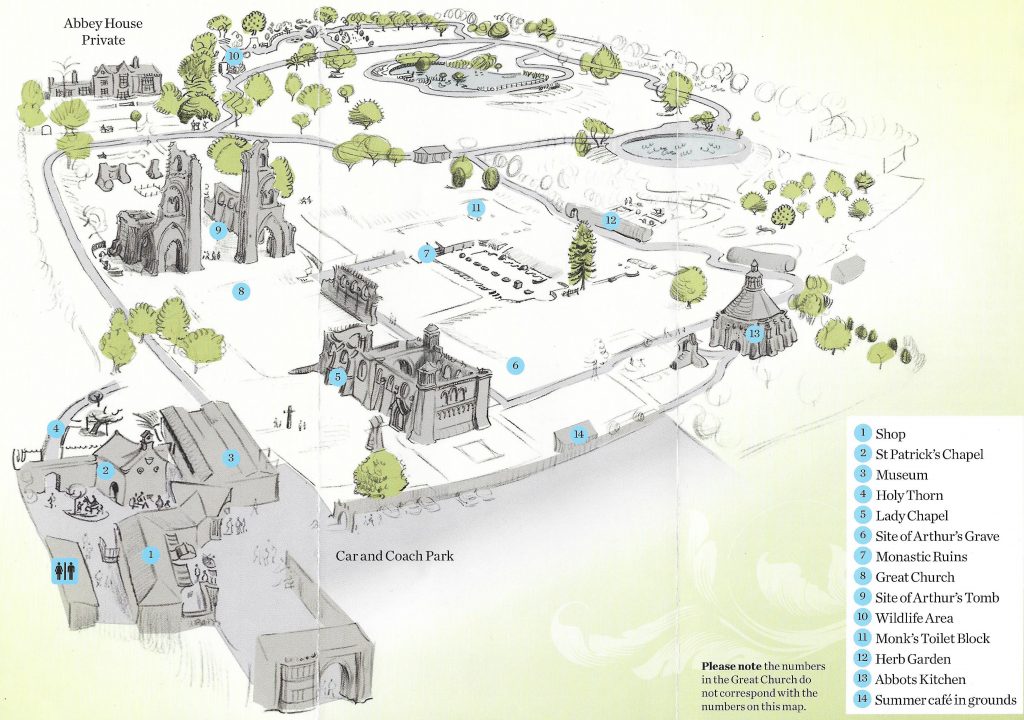

Even the smaller towns of Cirencester, the setting for Templar’s Prophecy, and Glastonbury, setting for Joseph of Arimathea’s Treasure, had markets, monasteries, and special services which drew people from outside. The tiny village of Aust, setting for Effigy of the Cloven Hoof and Usurper’s Curse, was a terminus of the southernmost ferry from England to Wales. Many people passed through Aust on their journeys between England and Wales.

The cities usually had walls for defence, and the main streets within the walls were often those that led from the principal gates. Along these main streets, people who could afford it lived in nice three-storey buildings which were long and narrow. This was the case for Lady Apollonia in Memento Mori. She lived in Windemere House on West Gate Street in Gloucester. The ground floor was sometimes used for commercial purposes with the upper floors providing residential space. As one got away from these finer parts of cities, the buildings were smaller, the lanes were narrower, and everything was less attractive.

Churches dominated the landscape of many urban areas. The cathedrals in Exeter and Worcester were massive compared with buildings around them. The same can be said for the monastic churches in Gloucester, Cirencester, and Glastonbury. Even in the village of Aust, the parish church sits at a high point and stands in a dominating position over the village. All the churches in my settings, except the monastic churches in Cirencester and Glastonbury, exist today and are still prominent in the modern landscape. In medieval times, there were walls around many of these church and monastic precincts. A castle may have occupied a tenth of a city’s area. Half the area within a city’s walls was often devoted to religious institutions and the castle. This meant that space for residents could be very precious.

The amount of the landscape in the vast countryside with trees was about seven percent, much the same as today. Yet, the woods were carefully managed in medieval times because people were very dependent on wood as a fuel and for other purposes. Some wood had to be imported from Scandinavia and other places for special purposes because the number of varieties of trees in England was limited.

The fourteenth century landscape of England was affected by various factors beyond the control of man. For example, the mean temperature dropped by one degree Celsius between 1300 and 1400. This doesn’t sound like much, but it changed England from a country which produced much wine in 1300 to one that could only import that beverage a hundred years later. The climate change resulting from this temperature drop sometimes brought too much rainfall and a host of related problems such as crops rotting in the fields.

Another factor on the changing landscape was the series of attacks of plague visiting England starting in mid-14th-century. The plague reduced the population by a third or more which meant that some farmland had to change its use to grazing for lack of manpower to tend crops.

Rivers and harbours sometimes silted up causing devastation to some towns. At the same time, reclamation of lowlands in the fens of East Anglia and in the Somerset Levels changed wetlands into farmland. This was occurring around Glastonbury at the time of my fifth novel, Joseph of Arimathea’s Treasure.

London does not have a major role in my first six novels, but it does play a significant part in the forthcoming seventh book, Usurper’s Curse. Therefore, I will mention its relationship to the landscape. I have already indicated that it was more than three times larger than any other city in England. It was also richer, more vibrant and polluted, and most powerful, colourful, violent, and diverse. The largest cities on the continent were Bruges, Ghent, Paris, Venice, Florence, and Rome, all with at least 50,000. London is the only English city that can be compared with these. Also, Westminster which housed some government functions was connected to London by the Strand. Yet, much of the government was itinerant. King Richard II held his parliaments in various cities including Gloucester.