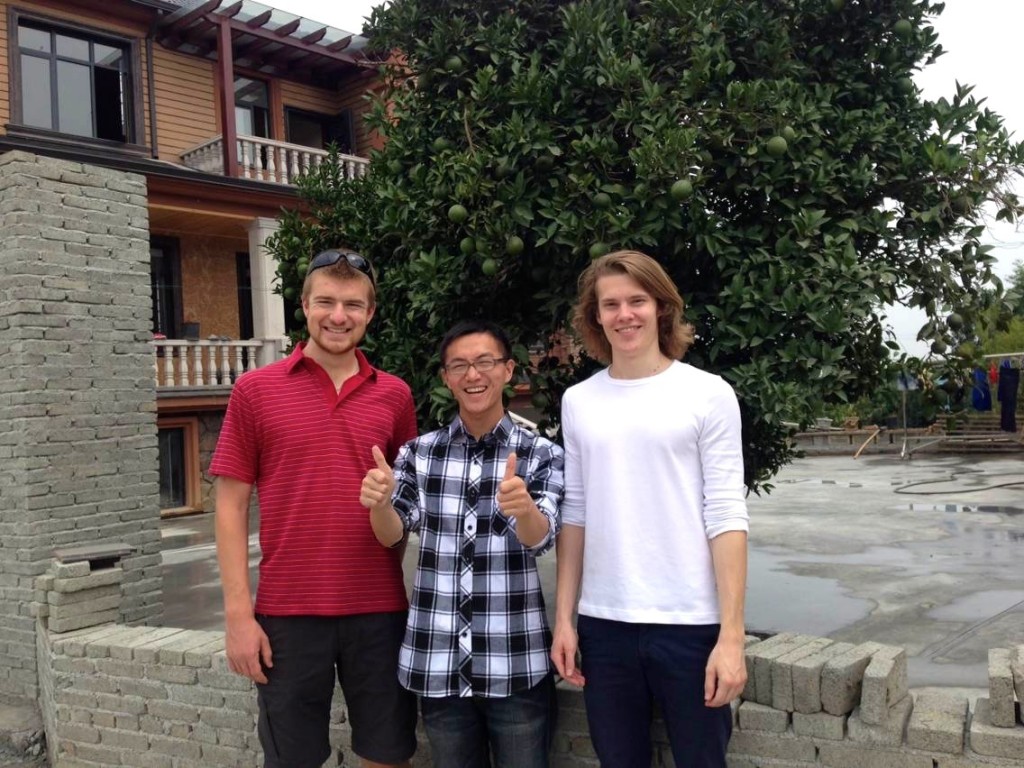

On Thursday morning Mr. Egg invited me visit his home. Mr. Egg (that’s his self-chosen English name) is a local who teaches English at a school near Yuquan Campus. We met a couple weeks earlier as Mr. Egg organizes informal weekly “English clubs” around Hangzhou. What I thought was going to be a couple hours at Mr. Egg’s apartment turned out to be an overnight trip into the Chinese countryside and an intimate look at (one form of) Chinese lifestyle.

We used Hangzhou’s extensive bus system to get out of the city. At one point where we switched buses we met up with Mr. Egg’s girlfriend, Sue, a nurse in Hangzhou. The Hangzhou bus system operates very similarly to those in the United States, with the exception of personal space—during rush hour many buses are packed to the doors. On our hour long journey into the countryside the bus “played” leap-frog with mountain bikers and moped riders. The bus stayed on a high way intermittently broken by stop lights. Besides in Beijing I haven’t seen any roadways around Hangzhou that would qualify as interstates, so even when the roads are not crowded the traffic is slower than in the U.S.

From a countryside bus station we took a brief taxi ride to Sue’s family home. When we arrived her parents were cooking lunch in a make-shift outdoor kitchen. Behind the kitchen her family’s new home was being built. We took a brief walk along the narrow lane around the neighborhood. Almost every home had a dog (for scare off thieves Mr Egg told me) and chickens roamed freely. Ponds, small vegetable patches, crumbling brick walls, groves of bamboo were wedged between houses and small fields of tea trees.

The rural homes were actually quite surprising to me. First off they almost all lacked any sort of grassy front yard which was instead almost wholly paved over. The homes themselves were quite large (I’d estimate +1,500 sq. ft.), built on a roughly square base, two or three stories, and with rather fancy exterior decorations. I wonder if the rather opulent exteriors had to do with the notion of “face”? The homes were also built entirely of concrete—almost as if they were a mini apartment.

Sue’s family was welcoming and seemed very relaxed, unfortunately communication was limited as it had to be translated by Mr Egg. Lunch was quite a feast, which Mr Egg emphasized was natural and organic—much of the produce had been grown by the family! Interestingly both at Sue’s and at Mr Egg’s we ate at different times from the parents (and grandparents). The food was far more than we could eat (and given how it was prepared I doubted it could be easily saved for leftovers). While I prefer not to waste food, I expect that over abundance of food was a purposeful way to honor guests and show one’s “wealth.”

Although Mr Egg referred to Sue as his girlfriend, they are what we’d call engaged, (Mr Egg refers to Sue’s parents as his in-laws). I learned that they will get married next year when Sue’s family’s home is finished. According to Mr Egg their “engagement” came by visiting both sets of parents and seeking their approval. Therefore “meeting the parents” is a pretty serious affair in China. Weddings (or at least Mr Egg and Sue’s) will have no formal service but instead be comprised of fancy dinner gatherings for friends and family at both of the family’s residences. I also learned that cohabitation is not frowned upon in China.

After lunch we took a taxi to Mr Egg’s small town where his father picked us up in a new Lexus SUV. We stopped by the family bamboo mat factory to move some mats inside in case it rained. The factory was worn but well kept, reminding me of the canneries in Alaska, and a pallet of boxes stamped with ‘Made in China’ was a quick reminder of how globalized even small businesses have become.

Mr Egg’s grandparents live with his parents in a large home nestled between steep bamboo forested hills. Actually, their old home still stands next to their new one. The old one is used as a garage for laundry, moped storage, and the old fireplace-heated bathtub. The interior of the house was surprisingly empty, exposed CFL bulbs often hung from cords poking out of the peeling and dirty plaster, cooking was done between a gas stove and woodfire heated wok, while a big flat screen TV broadcast CCTV the entire time.

Between meals we were offered tea along with nuts, grapes, dates, and dragon-fruit. After a dinner with similar food to lunch we visited Mr Egg’s aunt who lived just down the road and talked with her for a while. I asked Mr Egg about the Hong Kong protests, he was aware of them and seemed passively supportive, insinuating that democracy was probable eventually in China. It makes sense I guess, while China is economically expanding most people (such as Mr Egg) have little urge to disturb the political norm.

I never got the impression that countryside life was declining (whereas American small towns often seem to be struggling)—simply the job and entertainment offerings of cities were so much larger. Mr Egg felt bored at his family home. A funeral had taken place earlier in the day and Mr Egg told me briefly about it although his vague explanation exposed the growing distance of the younger generation from the traditions of his parents.

Overall I found the trip to be fascinating, from the style of countryside homes to the interactions of multigenerational households, to the focus on food as the center of hospitality in what was otherwise a very casual setting.

written 10/5/2014

Mr Egg’s family home

Dragonfruit!

Leave a Reply