Author: Emily Nelson

Location: Hirakata, Osaka, Japan

Japan is known for its courtesy. As a student living here, there are many examples of this. Every morning when I leave the dorms, several guards are stationed out front, greeting people as they enter and exit the premises. This is less for security than it is for giving directions, but nonetheless, the human interaction is still nice. When speaking to someone who you are serving or who is of higher rank than you, more polite language, called keigo, is used. And of course, bowing is very much still alive in Japanese social customs: The lower and longer you bow, the more respect you give. As someone who has now been living in Japan for a while, I would like to share my own experience with mannerisms here, as a (kind-of) Japanese person, if you will.

Most people here are very polite, as expected. There are few instances where I’ve come across anybody disrespectful. As a country that is arguably more collectivist than the United States, Japan values social relationships and harmony more. In the past, as someone who has been very fed up by rude people back home, coming here is almost like a breath of fresh air. But as I’ve grown older, I’ve come to question whether this is really better. Being respectful to others is a social expectation, and therefore most people follow it likely because they don’t intrinsically want to, but because they feel they have to. How many people are genuinely happy to be so agreeable all the time? While there are certainly people who are, others are may be acting. So are relationships really valued more in a collectivist culture, or are they simply the result of social conditioning? Maybe a mix of both? It seems that to gain social harmony, Japan has given up some genuineness in the process. It appears that each society chooses what it finds more important, genuineness in more individualist cultures or harmonious relationships in those emphasizing collectivism.

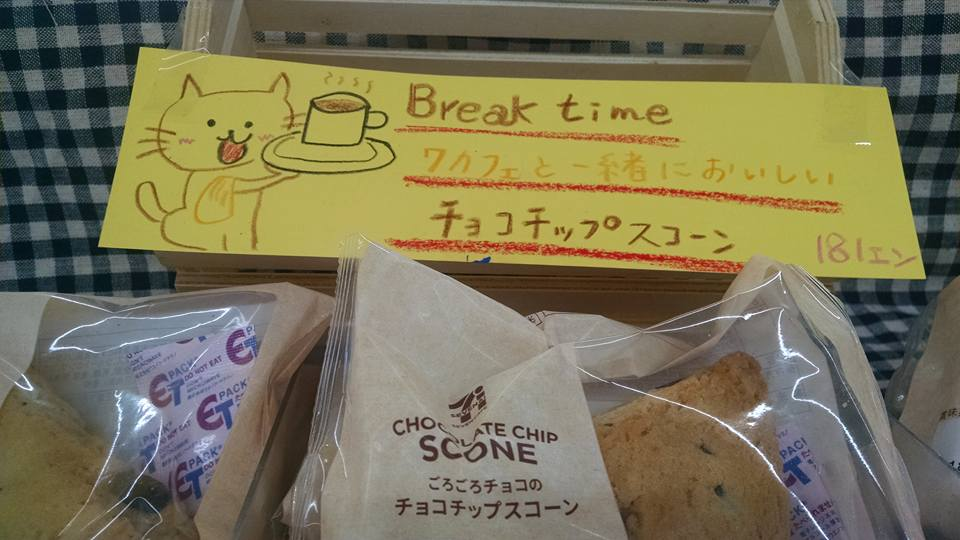

Seen at 7-Eleven. Japan really knows how to market to people.

I’ve alluded before to my appearance, or looking native enough to be addressed in Japanese. While I appreciate this, as it gives me the chance to practice speaking, it also sets off some minor alarm bells in my head, and not just because I don’t know how to say a lot of things. But why, you may ask? I had to ask myself the same. This is what I determined: Because I appear to be Japanese, it is expected that I adhere to the social rules and present like a citizen of this country, which holds more collectivist than individualist values. However, that’s not accurate of myself, as I’ve been removed from my country of origin for many years now, living in an area that encourages personal achievement more. This study abroad trip is the longest I’ve ever spent in Japan, and the first time on my own. As a result, I feel a constant social pressure to be more Japanese, and therefore more socially acceptable, even though my appearance does not match my experience. This was brought to my attention by a friend, who stated that I seemed too concerned about rules here. I think, however, that we’re all concerned about rules, it just depends on which type of culture we grow up in and our relations to them. Nonetheless, I do agree that I am overly concerned, otherwise I wouldn’t be writing this!

Regardless of my opinion on these topics, I think that this is certainly a testament to the benefits of studying abroad. It certainly helps one understand their place in the world and how their home has shaped them. In a new place, one’s upbringing stands out clearly and invites more understanding to one’s identity as they adapt. I hope this helped you understand differences in perspective as much as it did for myself.

Cherry Blossoms!

Disclaimer: This writing is influenced by a work I am reading in psychology class called Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind by Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov. The interpretations I present are in part due to me learning about individualism/collectivism in this book.

Leave a Reply