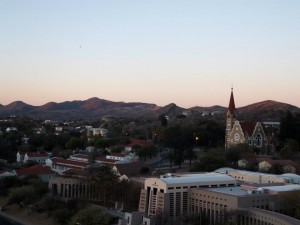

For our final projects this semester we were assigned to do an integrative project that would encompass the things we’ve learned in the past few months. Some of us chose to do games, some made videos, and others used a straw building activity as a metaphor for building a nation. I was impressed with how creative our group was, at the amount of information we have really absorbed, and the critical thinking skills we’ve developed. I found one student’s project particularly inspiring and wanted to share it. This person is from South Sudan so he has an unique perspective and being from the new youngest independent country in the world he wanted to draw parallels between their struggle to build a nation and the second youngest, Namibia’s struggle. I think this letter will give you a good idea of the obstacles Namibia has encountered in the past few decades and the things we’ve been taking an in depth look at on this trip. As we have, I am sure you can see these themes in the struggles for equality in many nations, including our own. Here is his letter to Namibia, if he were South Sudan:

For our final projects this semester we were assigned to do an integrative project that would encompass the things we’ve learned in the past few months. Some of us chose to do games, some made videos, and others used a straw building activity as a metaphor for building a nation. I was impressed with how creative our group was, at the amount of information we have really absorbed, and the critical thinking skills we’ve developed. I found one student’s project particularly inspiring and wanted to share it. This person is from South Sudan so he has an unique perspective and being from the new youngest independent country in the world he wanted to draw parallels between their struggle to build a nation and the second youngest, Namibia’s struggle. I think this letter will give you a good idea of the obstacles Namibia has encountered in the past few decades and the things we’ve been taking an in depth look at on this trip. As we have, I am sure you can see these themes in the struggles for equality in many nations, including our own. Here is his letter to Namibia, if he were South Sudan:

An Open Letter from Sud to my friend Namib.

Dear Namib,

It has been an absolute pleasure and joy to see you during the past 3 months. I’ve enjoyed visiting your many national historical sites, game parks, and conservancies. I’ve enjoyed our days filled exploring topics in religion, politics, history, and even our occasional outings to meet and greet speakers in order to expand our knowledge. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed learning about and practicing yoga while here. Although all of these events brought me great joy, there were some things which disturbed, confused, and even shocked me.

I saw you turn away children and shut down schools in the north, I even saw you care more about money then education, when u stopped university and secondary age children from taking exams and getting results due to lack of school fees. I saw children born out of the struggle in exile suffering and carried away from the lawn of the national assembly as they tried to voice their concern, I saw you harass and intimidate locals into doing what you wanted. A random guy on the streets even stopped to tell me he was unhappy with the failure of the high court to decide on their election petition to the Supreme Court in a timely manner. That’s not even the worse one of the guys told me a few years after you moved out from under your parents roof, you subject our friends and families to torture and death while in exile in Angola, and to this day you still have not confessed or owned up to it.

What is going on Namib, as your friend I am very concerned.

I’ve even heard some people have tried to summon you to the ICC department of Human services. Don’t you remember that’s the same department which ruled your parent’s treatment and occupation illegal?

A U.N. Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous people named James Anaya even pointed out that all of the indigenous groups he has met with continue to suffer injustices as they have not seen the promises and benefits, which independence from your parents promised.

I know our upbringing was not the best, but it is no excuse for the neglect oppression, and injustices which I have seen while here.

Do I need to remind you about the hardship, discrimination, and oppression which we endured under our parents roofs? The blood sweat, and tears shed to realize our freedom. Do I need to remind you of the unequal treatment, subjection to unfair labor, housing, and opportunity your parents afforded you? How they made you feel dumb, inferior, and told you, you had no history, and that keeping you apart from the others was for your own good and how they made you carry your I.D. card in certain parts of the house.

I know you remember these terrible times.

I was under my parents roof for much longer, and in that time we did not talk as much. But I know you heard about the persecution and oppression which I received from my parents. How they tried to force their religion, values, and way of life down my throat. The worst of which was heard around the world when they killed, tortured and maimed our friends in Darfur. I don’t know if you heard but during that 50 year struggle under my parents’ roof, I really started to have internal struggles with myself. I struggled about whether to liberate everyone from my parent’s oppression, or just get myself out from under their roof. This dilemma really ate at me, and when I wasn’t actively resisting my parents, I broke out in internal strife and all out chaos within myself almost to the point of self-destruction.

We were so Strong back then Namib, I remember you marched and boycotted, demanding to get out from under your parents. Do you remember hector Peterson, Steven Biko, and the many students and friends whom died fighting and demanding your release? I do! Do you remember when our friend Luther who finally had enough, and took a stance against your parents, oh how he condemned their actions, after our friends in the I.C.C. department gave their verdict?

We had lots of friends and family who helped us to survive and endure those long and trying years under our parent’s roofs.

In your absence Uncle Tom and his many friends really stepped up and helped me endure my internal struggles and my resistance against my parents. Uncle Tom played a very vital role in bring about a comprehensive peace agreement in 2005. His friends Amnesty, UNHCR, and I.R.C provided me with and still continue to provide me with vital services including healthcare, child survival programs, education, and sexual violence aid and prevention projects. When I visited Uncle Tom in 2006, he gave me a Black cow boy hat, which I never take off or go anywhere without, as a sign of my gratitude and appreciation for all of his support.

Please remember the long hard road we traversed in order to get where we are today.

Do you not remember the promises we made to each other about how we wanted to live our lives once we were out from under our parents. How we wanted to live them through respect, understanding, and acceptance of all people regardless of race, religion, Ethnicity, tribal affiliation, or sexual orientation. And how we vowed to never turnout like our parents.

We even wrote it out in our supreme plans, oh how brilliant our supreme plans were. I can remember yours boosted by many people as one of the most inclusively liberal plans on earth. Especially with your clause pertaining to or should I say lack thereof a death penalty. Oh how our plans looked so spotless to the many onlookers. I know my plan is only an interim one due to my recent emancipation only a year and half ago from my parents, but I’m still quite proud of it. I’ve made sure to include our respect principles especially pertaining to religious practices.

I never want anyone to experience the turmoil I went through, the 2 million friends dead and the 4 million displaced in that long 50 year resistance against my parents.

I’m Sorry to labor on for so long old friend, but this letter is also helping me to remember and come back to those plans we created in the days of struggle. Writing this has forced me to really take a critical look inward, and sorry to say I’ve been a hypocrite.

If you were to come visit me you would not only see a lack of respect for freedom of speech, but sever mal treatment and torcher of those who openly oppose. Our brother Mr. Deng Athuai, chairman of the South Sudan Civil Society Alliance, was abducted and beaten a year into my independence, because he openly spoke out and criticized government officials on corruption. That’s not even the worse, I thought I was finished beating myself up when I got out from under my parents. But recently new problems have arisen, and they almost take me back to the brink of self-destruction within myself. Even though I’m only a year and half out, I have not made sufficient plans to meet the needs of my people.

I have not taken the initiative to put education first so everyone can learn about and hold the supreme plan as the rule of law.

Please give the teachers I have seen striking a raise, so they may effectively teach all of the children about our supreme plans, and thus hold us accountable to our plans, so they may speak out and let us know when we have strayed without fear and so that they will know their actions and participation and criticisms are grounded in our supreme plans which rule the land.

So Sorry for the short notice and having to communication via letter, I wish I had the time to say farewell face to face, but I got an urgent call this morning to return and start the development process ASAP. There’s roads, hospitals, and schools to be built. Writing this letter has put me back in my right state of mind.

I felt like I had to say something or as our main man Lupe would say. It would have been so loud inside my head, with the words I never said. I will thoroughly miss the great food, conversations, and friends at the center for global education not to mention the many friends from basketball, Wadadee and our times at Kapana Soul Sessions.

Once again you’ve opened my eyes to so many new perspectives and possibilities.

But please keep in mind our past, I know we can’t do anything about it, but we can do something about the future that we have.

Sincerely your friend,

SUD

For one of our last development classes we went to GreenSpot organic farm in Okahandja. Manjo Smith, who runs the farm, gave us a thorough tour of the property before serving us a delicious organic breakfast cooked on their very own solar stove.

For one of our last development classes we went to GreenSpot organic farm in Okahandja. Manjo Smith, who runs the farm, gave us a thorough tour of the property before serving us a delicious organic breakfast cooked on their very own solar stove.

South Africa recently opened their borders to Monsanto’s GMO seeds, and the backlash from environmental activists has been enormous. The strain of corn being used in South Africa contains one of the two active ingredients in the infamous Agent Orange, also a product of Monsanto. The Green Times reports that exposure to 2,4-D corn has been linked to non-Hodgkins lymphoma and has been shown in studies to cause birth defects, neurological damage, and interference with reproductive organs. Unfortunately anti-GMO activists have had difficulty actually proving the link between Monsanto GMOs and cancer.

South Africa recently opened their borders to Monsanto’s GMO seeds, and the backlash from environmental activists has been enormous. The strain of corn being used in South Africa contains one of the two active ingredients in the infamous Agent Orange, also a product of Monsanto. The Green Times reports that exposure to 2,4-D corn has been linked to non-Hodgkins lymphoma and has been shown in studies to cause birth defects, neurological damage, and interference with reproductive organs. Unfortunately anti-GMO activists have had difficulty actually proving the link between Monsanto GMOs and cancer. South African activists are pushing petitions to ban Monsanto GMOs in the country. In spite of their efforts, Monsanto maintains a worldwide monopoly on the agriculture industry. Big money means big power and big influence in politics as we’ve seen year after year through Monsanto’s powerful lobbyists and lawyers. I agree with Smith though, the power to the change the system lies in the hands of the consumers. Slowly, but surely, I think consumers will open their eyes to the damage of Monsanto’s chemicals and change the demand “back to basics” and the innovative technology that organic farming entails.

South African activists are pushing petitions to ban Monsanto GMOs in the country. In spite of their efforts, Monsanto maintains a worldwide monopoly on the agriculture industry. Big money means big power and big influence in politics as we’ve seen year after year through Monsanto’s powerful lobbyists and lawyers. I agree with Smith though, the power to the change the system lies in the hands of the consumers. Slowly, but surely, I think consumers will open their eyes to the damage of Monsanto’s chemicals and change the demand “back to basics” and the innovative technology that organic farming entails.