Author: Mia Casas

Location: Santo Domingo, Costa Rica

Pronouns: She/Her/Hers

If you are thinking about studying abroad at Valparaiso’s Study Center in Costa Rica, here’s a detailed guide that outlines everything from class structures, internship options, housing accommodations, and other notes that may help you in your decision to study abroad in Costa Rica. Originally, I wanted to answer these questions all in one document, but I realized there’s just so much that it would be better to split up the topic into two parts — academics and recreation.

What is a study center?

A Valpo study center provides more resources to students during their time abroad. A defining characteristic is a local, on-sight Valpo director who works one-on-one with students to provide classroom instruction, group excursions, local directions, etc. If there is anything else you may need help with, you will always have someone easily accessible to ask. Included with the cost of the study center fee are housing arrangements, whether it be in a homestay or residence hall. For Costa Rica, students do live with a host family, and typically there are other students from Valpo that will form your entire cohort. More information about the different study abroad programs available at Valpo can be found here.

What classes do you take in Costa Rica?

Everyone is automatically enrolled in three classes:

- Spanish Grammar class

- Spanish Conversation class

- Ethnology and History of Costa Rica

Before you enroll for your Spanish classes you will complete a placement exam to determine your level of Spanish. The levels are assessed as A, B, or C; A being the beginner level and C being the most advanced level. From there, each section is split into section 1 and section 2, the latter being the more advanced course. Truthfully, your performance on the placement exam does matter, but the number of students available for each class session plays an important role for the university. I say this because, for our group, we were all placed either in B1 or B2 and no C level classes were offered, initially. This also means that you may be in a course where each students’ Spanish-speaking capabilities vary, but regardless we were all placed in the same class for the sake of class availability. Once you start classes you will realize that the class size is very small, approximately 10 students or less, so it is a good environment to ask a lot of questions.

The structure of the classes is designed to be an intensive course. You will take both Spanish classes at the same time, starting at 8 am and finishing just before 1pm, for four weeks. Between classes you have a 30-minute break. This may not sound too bad, but you may find yourself waking up as early as 5:30 am so you can catch the 6:40 am bus to UCR. But, after just four weeks you will have earned 6 credits of Spanish! Another unique thing is that this Spanish class is exclusive to foreign students, so you have the chance to meet people from different parts of the world and even form friendships.

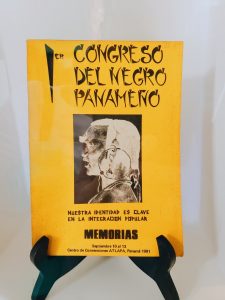

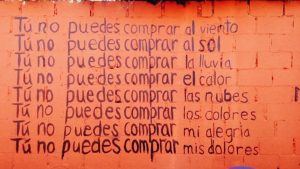

For the other course, you study with Heidi Michelsen at Casa Adobe, Valparaiso’s Study Center (also known as the Praxis Center). You begin this course as soon as you arrive to Costa Rica, and it lasts for 9 weeks. The first four weeks are intense because you meet almost everyday for almost the whole day. The good thing is that the topics of the course are interesting, Heidi frequently invites guest speakers, and group excursions are built into the curriculum. Then, on the fifth week the cohort does a study tour. This year we went to Panama, in previous years students travelled to Nicaragua, but, since last year, it has been too dangerous to travel there. Heidi intentionally designs the program so that students are exposed to various walks of life — from urban life, to rural life, to indigenous life. So, just as you will do in Costa Rica, you will experience different lifestyles in Panama. Once you return to Santa Rosa, you will start your Spanish classes. At this time, you will meet less frequently for Heidi’s class, typically just once a week. After the first 9 weeks, students typically begin an internship, but there are other options available, as well.

Interested in other miscellaneous class work? Heidi does her best to arrange whatever classes you may need to take abroad, and each member of my cohort has taken various elective courses. Two of my classmates enrolled in a Theology course about ethics at La Universidad Bíblica Latinoamericana, which is a theology course purely in Spanish. The course lasts 15 weeks, spanning the entire length of our program, and ends in December. They meet for a few hours in the evening only once a week. My other classmate decided to forfeit doing an internship and continue taking classes at UCR. He was initially placed in B1 and has progressed into the C1 course. He is also taking another class with Heidi about the Sociology of Healthcare in the evenings once a week. As for me, after classes at UCR I began a 3-week course on Central American literature with Latin American Studies Program, a study abroad program for various Christian colleges in the US. I am also completing an independent study course on Liberation Theology with Heidi, and an independent study for my International Economics and Cultural Affairs Senior Seminar with my professor at VU. Don’t worry about buying any textbooks for any of these classes. As far as I could tell, all the materials are provided for students.

What are the internships like?

After the first 9 weeks, students typically begin working with an internship of their choice. Most are business related or medical related. I’ve included a link to the list of internships available as of August 2019. If you have a clear idea of where you would like to work, talk to Heidi so she can help you. We always joke around that Heidi has connections everywhere, and it’s true.

Veronica Campell has worked in the neighborhood of La Carpio, a marginalized community of predominantly Nicaraguan refugees and migrants, translating locals’ stories into a book that recounts monumental moments of community members.

In general, I would say your internship is what you make out of it. The work culture is very different here, so it probably won’t match your expectations of a typical internship, based on US standards. For one, ticos (Costa Ricans) have a different concept of an internship than we do, that is to say, they don’t often employ interns. So when you arrive, you will have more personal responsibility and liberty to outline what projects you choose to participate in at your internship. While there, you may also realize that the work environment is more relaxed, and it may feel like you have a lot of down time. Use this time to talk with your peers and/or supervisors and learn more about the company culture and Costa Rican culture, in general.

Veronica works alongside The Costa Rican Humanitarian Foundation, which offers a variety of community enrichment programs.

A lot of this information will be explained by the Study Abroad Office and/or Heidi Michelsen, the Costa Rica program director. However, I hope it helps having the details provided here for you to read thoroughly. I based these questions on some things I had wondered before going to Costa Rica, so hopefully this clears up any doubts! If you ever have a question in the future, I’d be happy to answer any of your questions via email at mia.casas@valpo.edu

The international Spanish students took a field trip with their UCR Spanish professors to breakfast and the Jade Museum.

Veronica and I befriended students from the Netherlands and Norway, and have enjoyed going out for dinner, going to the theater, and getting to know Costa Rica together.